Introduction

In the last two decades, there has been an increasing application of the concept of social capital in various fields of public health; therefore, social capital has been frequently used in health sciences1. However, social capital is a controversial concept, with extensive debate on its definition and objective measurement2. The most critical and practical limitation is measuring social capital in clinical and epidemiological studies3.

The construction of an instrument to quantify social capital is a complex process because of the nature of the concept4. Nevertheless, it is necessary to obtain reliable construct measurements for clinical and epidemiological studies5. Social capital is widely understood to be the structural, relational, and cognitive characteristics of social interactions that facilitate concerted or coordinated actions and collective learning4. It can also define how institutions, relationships, attitudes, and values mediate interactions among citizens and support economic and social development6. Social capital refers to the resources that citizens and groups access through constructed social networks (1). Finally, it is currently defined as a set of direct or indirect resources that results in social interactions between people and groups7. Some authors recognize three types of social capital: structural, relational, and cognitive. While others recognize only two types of social capital, they make cognitive and relational social capital synonyms for the common elements between both concepts8.

According to the context, social capital can be divided into three types: bonding, bridging, and linking2,9,10. Bonding social capital refers to the resources available within the network for relationships between individuals with similar characteristics such as age, social class, or ethnicity/race10. Bridging social capital describes the social resources that people with different sociodemographic characteristics can access1. Linking social capital refers to networks of trust and respect that connect people and groups through formal institutions with authority or power9.

In addition, one pair of types of social capital is relevant to health research. First, cognitive social capital refers to the perception of trust, reciprocity, honesty, truthfulness, and support from other people8,11,12. Structural social capital refers to formal structures in which citizens can develop ties and social networks and participate in civic associations and events1. These concepts are particularly relevant because of the direct and indirect relationships between cognitive and structural social capital, and the physical and mental health of different human groups13,14. De Silva et al.13 reported an inverse association between cognitive social capital and common mental disorders, anxiety, and depression. Similarly, the authors observed a moderate inverse relationship between children's cognitive social capital and their mental disorders. Similarly, Riumallo-Herl et al.15 reported that, in people with diabetes or high blood pressure, the perception of physical health was inversely related to social capital.

From a psychometric perspective, social capital has been measured in different ways and is sometimes only valid and reliable. The questions or items of these instruments only evaluated the validity of the authors’ appearance. Therefore, the available measurements for social capital are inconclusive and unable to quantify accurately the complex dimensions raised in theory2,12,13. Several English and Chinese instruments have been designed, and these measurement scales comprise different numbers of items and purposes. Psychometric tests of reliability and validity were carried out using The General Capital Social Scale16, Bonding Social Capital Scale17, Personal Social Capital Scale18, Social Capital Investment Inventory19, and Trust Scale based on Social Capital in Spanish20. Wang's scale is a Spanish version21. Other sets of items have been used as scales without formally exploring their psychometric performance in other studies. Without intention, nomological validity was achieved by exploring the correlations with other variables of interest. Martin et al.22 concluded that elevated social capital, particularly reciprocity among neighbors, was related to the low risk of household food security. Sapag et al.23 reported that neighborhood social cohesion, measured by trust and reciprocity, was related to better health self-assessment within a low-income community in Santiago, Chile. Alvarado et al.24 observed a negative correlation between scores for social capital and psychological distress, anxiety, and depression among Chilean workers. Holt-Lunstad et al.25 reported that solid social relationships could reduce the mortality risk by up to 50%.

In the present study, seven face validity items were chosen to measure cognitive social capital, most related to mental health13,24. Martin et al.22 took these items as a proxy instrument for measuring the social capital of a scale developed by other researchers to quantify social cohesion and trust26. Martin et al.22 did not report any psychometric indicators for the set of items. Then, the current authors named the tool "Cognitive Social Capital Scale" (CSCS). The CSCS has several questions with other instruments exploring cognitive social capital1,2,11,12. A validity test explored internal consistency and used exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The internal consistency reliability of tests represents the average of the correlations between the scores of scale items27,28. On the other hand, factor analysis is technical to assess dimensionality, a mathematical way of testing whether the items are distributed in the theoretically proposed factors or dimensions29,30.

The validity and reliability of the measurements are essential for the internal validity5. It is necessary to have blunt instruments to measure social capital, which show acceptable or excellent psychometric performance12,31. Repeatedly using the same instrument makes it possible to make more precise comparisons of findings in different studies and contexts31. This study aimed to assess the reliability (internal consistency) and validity (exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses) of the CSCS among adults in Colombia's general population.

Methods

Design: Validation analysis was conducted without external reference criteria. The study was nested in a cross-sectional study that included several measurement scales, including a version of the CSCS. Validation studies are also known as methodological studies because they explore the usefulness of some measurements or quantification of concepts. There are criterion-referenced validation studies that provide the best available objective measurements to test the performance of the scale. These objective measurements are rare for the measurement of social and psychological concepts. Studies without reference criteria used tests or statistical techniques to approximate the reliability and validity of the measurements, as in the current study, in which exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses and internal consistency were performed.

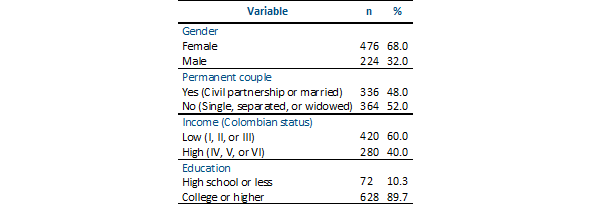

Participants: Seven hundred people residing in Colombia completed a questionnaire. This sample size is acceptable for carrying out exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses with a minimum acceptable error in the estimates made; in general, samples with more than 500 participants are recommended32. The participants were aged between 18 and 76 years (mean=37.1, SD=12.7). In frequencies and percentages, other demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Instrument: Participants completed the CSCS. This scale explores current perceptions of the relationships among neighbors. Each item provides four response alternatives from strongly disagree to strongly agree, rated from zero to three22. The translation and back-translation processes were based on international recommendations for a culturally adapted and linguistically equivalent translation33,34. Two independent bilinguals translated the items from English to Spanish. There were a few differences between the versions that were resolved by consensus. A third person translated the final Spanish version into English. There was a high agreement between words and linguistic equivalence. Caution was taken to avoid negative sentences that, in Spanish, tend to confuse the sense when answering35. Below are the items of the CSCS; they were headed with the phrase "In the block, residential complex, building, or neighborhood in which I live":

1. "People around here are willing to help their neighbours." (La gente está dispuesta a ayudar a los vecinos).

2. "This is a close-knit, or ''tight'' neighborhood where people generally know one another." (Las personas son unidas y generalmente se conocen entre sí).

3. “If I had to borrow $30 in an emergency, I could borrow it from a neighbor.” (Si tuviera que pedir prestado $50.000, en caso de emergencia, podría pedírselo prestado a un vecino).

4. "People in this neighborhood generally do not get along with each other." (La gente generalmente se lleva bien).

5. "People in this neighborhood can be trusted." (Se puede confiar en las personas).

6. If I were sick, I could count on my neighbors to shop for groceries for me.” (Si estuviera enfermo podría contar con mis vecinos para que hiciera algunas compras por mí).

7. "People in this neighborhood do not share the same values." (Las personas comparten los mismos valores).

Procedure: Information was collected by distributing an electronic questionnaire sent by email, WhatsApp, and Facebook to the researchers' contacts. The response period was limited to March 30 to April 8, 2020. In online studies, the highest response rate (approximately 30%) occurred in the first week and only improved with additional requests36. The questionnaire did not ask for the names or other identifying information of the respondents. All questions in the questionnaire were mandatory; consequently, the participants had to complete all items. This obligation was implemented to ensure the availability of complete and accurate data.

Data analysis: In the validation studies, the variables were part of the scale. Generally, the process of exploring item performance begins by calculating internal consistency. Internal consistency is a measure that summarizes the mean of the correlations between items on a measurement scale. It is a measure of reliability and, at the same, an indirect measure of validity. High internal consistency is a fundamental requirement of measurements; however, it does not guarantee good performance on all validity tests37. For instruments under construction, internal consistency values of 0.60 may be acceptable, but for more developed instruments, values between 0.90 and 0.95 are preferable5,38. Internal consistency was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha27 and McDonald’s omega28. Cronbach's alpha coefficient is the most informed reliability indicator; however, it has a main limitation: it starts with the assumption of tau equivalence. All items contributed similarly to the construct37. When the principle of tau equivalence is violated, McDonald's omega becomes a more accurate estimator of reliability28,37. These coefficients can be misinterpreted when calculated for multidimensional instruments because they erroneously overestimate the internal consistency owing to the number of items37. Currently, it is recommended to report at least two reliability indicators for one-dimensional measurements38.

Factor analysis was used to identify an underlying or latent factor in a set of items. Exploratory factor analysis is used to test the dimensionality of a scale, often misnamed construct validity, and attempts to mathematically demonstrate the theoretical dimensions of an instrument in the initial stages of construction39. Confirmatory factor analysis confirmed a previously suggested structure using advanced statistical procedures40. A researcher can expect up to two dimensions for a seven-item instrument, ideally one29,30,41,42.

Factor analyses were performed to test the dimensionality of the CSCS using the maximum-likelihood method. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index [KMO]43 and Bartlett’s44 sphericity tests were computed in the first step of the exploratory factor analysis. If the KMO is more significant than 0.60, and Bartlett's chi-square shows a p-value less than 0.05, it indicates that the items group a latent factor. Exploration can continue without guaranteeing utterly satisfactory findings. Subsequently, communality and factor loadings were observed, interpreted as other correlation coefficients, and indicated the magnitude of the relationship between the item and factor45.

Confirmatory factor analysis is used to confirm a previously suggested structure with advanced procedures of computing goodness-of-fit coefficients: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the 90% confidence interval (90% CI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and Standardized Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Under the best conditions, it was expected that chi-square with a probability greater than 0.05, RMSEA and SMSR with values close to 0.06, and CFI and TLI values greater than 0.89. At least three coefficients within the desirable values may be sufficient to accept that the analyzed data fit the theoretical model of the instrument evaluated46. The analysis was completed in the statistical program STATA 13.047.

Ethical issues: The research was supported by Colombian State University (Minute 002 of the extraordinary session held on March 26, 2020). The research followed the ethical recommendations for research on human subjects following the Declaration of Helsinki48) and Colombian legislation that disapproves the provision of any incentives to research participants49. All participants provided informed consent. Participants’ anonymity, respect for privacy, and handling of all the information recorded in the research questionnaire were guaranteed.

Results

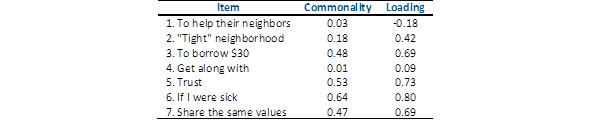

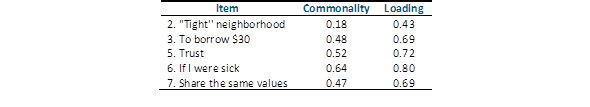

CSCS: The CSCS showed low indicators of internal consistency; the value of Cronbach's alpha was 0.56, and McDonald's omega was 0.69. The exploratory factor analysis showed that the seven items of the CSCS could retain a latent factor; the coefficients were excellent, Bartlett's chi-square of 1,224.3, df=21, p<0.01, and KMO index of 0.77. Nevertheless, Item 1 (helping neighbors) showed a negative loading value, and Item 4 (getting along) presented a very low loading. The commonalities and loadings of the CSCS are presented in Table 2.

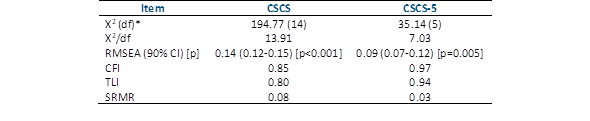

The eigenvalue was 2.84, explaining 40.88% of the total variance. In addition, confirmatory factor analysis showed that all the goodness-of-fit indicators were suboptimal. Thus, the hypothesis of a one-dimensional structure is rejected. Similarly, the possible performance of a two-dimensional structure was explored, and the results were unsatisfactory (these coefficients were omitted). The indicators for the one-dimension structure of the CSCS are listed in Table 3.

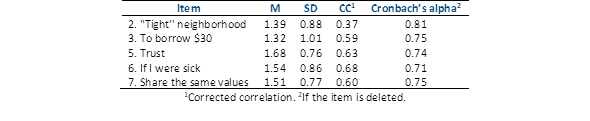

CSCS-5: After deleting items 1 and 4, this five-item version (CSCS-5) presented high internal consistency values; Cronbach's alpha was 0.79 and McDonald's omega 0.80. Table 4 presents descriptive information on the CSCS-5, mean, standard deviation, corrected item correlation, Cronbach's total score, and alpha if the item was omitted.

The exploratory factor analysis indicators suggested that the five retained items represented a latent factor or dimension: Bartlett's chi-square was 1,064.3, df=10, p<0.01, and KMO was 0.81. Confirmatory factor analysis of the CSCS showed acceptable coefficient values for a one-dimensional structure. Table 3 shows the goodness-of-fit indices for the CSCS-5 and the CSCS, and Table 5 summarizes the commonalities and loadings of the CSCS-5.

The eigenvalue was 2.79, explaining 55.88% of the total variance.

Table 4 Mean, standard deviation, correlation corrected with the total score, and cronbach's alpha with the omission of the item of the cscs-5

Discussion

In this study, the psychometric performance of the CSCS and CSCS-5 was reported. Only the CSCS-5 showed good psychometric indicators of reliability and dimensionality. The CSCS-5 is a tool with adequate internal consistency and a one-dimensional structure to assess cognitive social capital: the perception of trust, reciprocity, and support that people have about other individuals and institutions1,11,12.

In recent decades, interdisciplinary work between biomedical and social sciences has made it necessary to guarantee the validity and reliability of the measurements of social variables, which are usually approached qualitatively31. Generally, one-dimensional instruments are expected to show three out of five favorable goodness-of-fit indicators and high internal consistency reliability38.

CSCS-5 showed three out of five adequate goodness-of-fit coefficients for dimensionality. The most-reported coefficients are the Satorra-Bentler chi-square (with X2/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Standardized Mean Square Residual (SRMR). For the Satorra-Bentler chi-square, a p-value higher than 0.05 (with X2/df<5); RMSEA, a value of around 0.06; CFI and TLI, values higher than 0.90; and SRMR, a value below 0.0546.

Likewise, the CSCS-5 achieved two excellent internal consistency indicators: Cronbach's alpha of 0.79, and McDonald's omega of 0.80. Measuring construct instruments should present high internal consistency reliability, with values between 0.70 and 0.9538. It is necessary to report an instrument's internal consistency each time it measures variables because it can vary significantly between samples from different populations5.

The provision of a CSCS will facilitate new research on this issue. The lack of short, reliable, and valid tools to assess cognitive social capital has been a problem for conducting considerable research in the general population2,12,13. It is necessary to consider and evaluate cognitive social capital in the health sciences because it is related to mental health outcomes. The social determinants of health support that the physical and mental health of the population groups result from the complex interaction between individual, family, community, social, cultural, and institutional factors13.

This study demonstrates the performance of a short scale to quantify cognitive social capital using confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate the dimensionality of the CSCS. This technique is a robust multivariate psychometric analysis that identifies the latent factors underlying a set of items41. However, the technique still needs to overcome the practical difficulties of complex concepts, such as cognitive social capital1,4. The instruments must be adapted or modified as progress progresses, and the concepts to be measured clarified50. Moreover, given the sample collection technique, the test-retest reliability of the scales could not be established51. This measurement is essential to guarantee the total reliability of the measurements with instruments5. Similarly, an analysis of the device's dimensionality and reliability in other languages is required to make valid comparisons of studies conducted in different languages33,34.

Future research should test the quality of this instrument by exploring other convergent validity with other instruments that quantify the same construct, divergent validity with an instrument that theoretically and empirically does not show any relationship with the construct of cognitive social capital, and different forms of nomological validity, that is, the relationship with other unrelated contexts but theoretically associated with cognitive social capital5. In addition, based on item response theory, it is recommended to explore the differential functioning of the items to avoid the fact that the instrument can make a biased measurement based on a characteristic utterly external to the instrument. Some traits of the participating population included age, gender, or social or cultural background52,53. Unlike classical theory, item response theory is an alternative that allows for the identification of systematically biased response patterns from intuitive statistical analyses54,55.

Similarly, it is necessary to carry out other reliability measures; in the present study, only internal consistency was calculated, such as stability or test-retest reliability51. Furthermore, it is essential to establish sensitivity to changes in repeated measurements over time56. It is necessary to observe the instrument's performance using traditional pencil and paper measurements57. Finally, the validity and reliability of the CSCS-5 must be demonstrated in different populations according to age or other variables of interest5.

It was concluded that the CSCS scale has a one-dimensional structure that does not fit the data and has low internal consistency. The CSCS-5 exhibited a better one-dimensional structure and internal consistency. It is necessary to corroborate the present findings in future online and face-to-face studies of other Colombian populations. It is vital to have a valid and reliable instrument to evaluate social capital in countries with significant inequality, such as Colombia.