Introduction

Students are particularly vulnerable to psychological distress because they are exposed to a number of stressors such as academic pressures, economic concerns, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, and lack of family support1.

Mental health issues are currently considered one of the major challenges of public health as well as one of the main causes of morbidity among students2,3. In particular, medical students experience high levels of psychosocial stress because of continuous examinations, a relevant number of study-hours, pressure to succeed, and many other factors leading to higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide4.

Several studies have confirmed a high incidence of anxiety and depression among medical students with academic issues and family problems as the main associated factors5. A previous study conducted in South America by the Center for Clinical Epidemiology of the National University of Colombia, confirmed a high rate of mental disorders among medical students and a significant association with suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation6. Although medical students are usually very proactive after entering their course, half of them may report psychological distress very soon during training, as confirmed by recent evidence4. In addition, factors that may contribute to psychological distress are mostly related to the medical training itself: fear-based teaching, study overload, old and ineffective teaching methods (such as two-hour lectures), and even cases of sexual harassment or discrimination based on gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation7-10.

In Paraguay, medical students who report mental disorders frequently avoid reaching out for help. Reasons for this may include their fear of being rejected or treated differently by their peers, perception of being deemed unfit for practice, or rejection from their preferred specialty4,11. Given the recognized risk of mental disorders among medical students related to their training, we explored the perceptions of medical training and their own mental health among students at the School of Medical Sciences of the National University of Asuncion, Santa Rosa del Aguaray Campus, Paraguay, and described students’ reports of their own well-being and the impact of medical training on their mental distress.

Methods

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional, observational study that included medical students from the National University of Asuncion, Santa Rosa del Aguaray Campus, Paraguay, and aimed to describe their perception of subjective well-being and the impact of medical training on their own mental health.

The sample size was calculated using the epidemiological package Epidat. The minimum sample size was set at 113 medical students with a confidence level of 95%, an expected frequency of psychological distress in medical students of 20%, and a precision of 7.4%11,12. The sample finally consisted of 119 students, who participated freely and voluntarily through an electronic survey: it has been largely recognized that online surveys may provide significative findings as “in person” interviews13.

An adapted version of the "Perception survey on vocation, living and recreational habits, training and professional attitudes,” by Alonso Rodríguez and collaborators, was employed14. This instrument explores and describes the following dimensions: sociodemographic data (age, sex, year and semester of medical school, address, finances, work, reporting on relatives involved in medical careers), life and recreational habits (eating pattern, time management, physical activity, sleeping pattern, smoking, substance and alcohol use, hobbies, stable relationships, and social networks), perception of medical training (motivation to study medicine), vocation, and teaching resources (quality of teachers, practical training, and vocation for research), perception of professional activities (type of specialty and job opportunities).

The mental health of medical students was assessed using the CAGE (cut, annoyed, guilty, eye-opener) questionnaire, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)15, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2)16, with versions previously validated in Spanish in Paraguay11,17.

The CAGE questionnaire is a four-item tool validated as a screening instrument for lifetime alcohol use18. This screening instrument consists of four dichotomous response items addressing social criticism, feelings of guilt, morning drinking, and perceived need to stop drinking. Responses to the CAGE items are scored 0 for "no" and 1 for "yes" responses, with higher scores indicating alcohol problems. A total score of two or more is considered clinically significant. The normal cutoff for CAGE is two positive responses18.

The GAD-7 is a unidimensional, self-administered rating scale designed to assess the presence of symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Each item is scored from 0 to 3. The full-scale score ranges from 0 to 21. A total score of 10 or higher represents the cut-off for identifying cases of anxiety15.

The PHQ-2 assesses the presence of depressed mood and anhedonia during the past two weeks. These symptoms are measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, and 3 = almost every day). The PHQ-2 score ranges from 0 to 6. A total score higher than or equal to 3 indicates a significant level of depression, with a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 92%16,19.

Data were analyzed with SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) by the International Business Machines Corporation, version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the findings. Chi-square test, t-test, and ANOVA were used to establish associations. The findings were considered statistically significant with two-tailed p≤0.05.

Ethical considerations: This study was approved by the National University of Asuncion's School of Medical Sciences, Department of Medical Psychology (Paraguay). The data were treated with confidentiality, equality, and justice in accordance with the Helsinki principles. Participants did not receive any fees, and those requiring feedback from the survey were invited to write down their email addresses and receive information or specific helpful suggestions.

Results

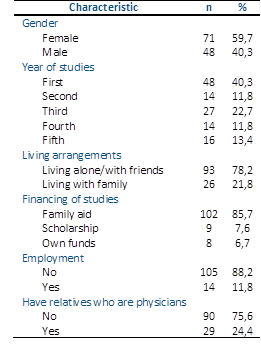

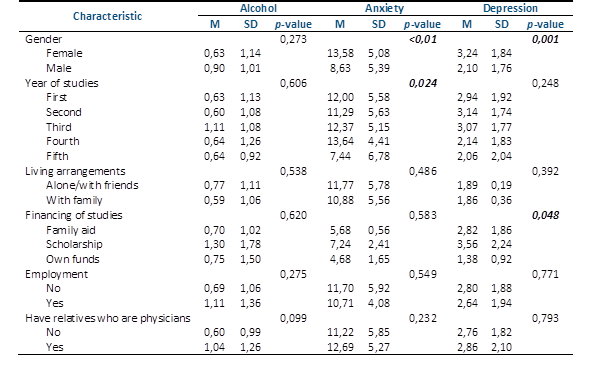

A total of 119 medical students from the National University of Asunción (Paraguay) were surveyed. Their ages ranged from 18 to 29 years, with a mean of 22.5±2.28 years old. The median age of the participants was 22 years and the most frequent age was 21 years. Of the participants, 59.7% were women, 40.3 % were first-year students, 78.2 % lived alone or with friends, 85.7 % financed their studies with family help, 11.8 % worked, and 24.4 % had close relatives who were physicians. Sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Regarding students’ living and recreational habits, 42.9% reported correct breakfast and 28.6 % reported correct diet. Of the participants, 56.3 % dedicated between two and five hours a day to study, 33.6 % dedicated more than five hours, and 10.1 % dedicated less than two hours. 38.7 % spent less than one hour a day on physical exercise, 23.5 % spent between one and two hours, 1.7 % spent more than two hours, and 36.1 % did not engage in any physical activity. Of the participants, 79.8% slept between five and seven hours at night, 13.4% slept less than five hours, and 6.7% slept for more than seven hours. Of the participants, 5.9% were regular smokers, 16.8% had tried cannabis, and 2.5% had used cocaine. In addition, 10.1 % had used stimulant drugs, and 18.5 % had used tranquilizing drugs. In addition, 15.1% consumed stimulant beverages, 58% regularly self-medicated, 65.5% did not have a steady partner, 76.5% studied with their cell phone next to them, and 99.2% regularly used social networks.

Regarding the perception of their medical training, students reported that they decided to study medicine for the related professional image in 47.1%, 26.1% accessed the School of Medical Sciences because of their life experiences, 11.8% because of doctors’ standard of living, and 10.1% because of illnesses in their own family. A total of 84.9 % of the participants reported that they had lost their social lives because of medical training. Among the students, 43.7% had seriously considered dropping out of medical school.

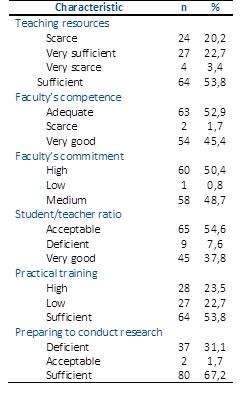

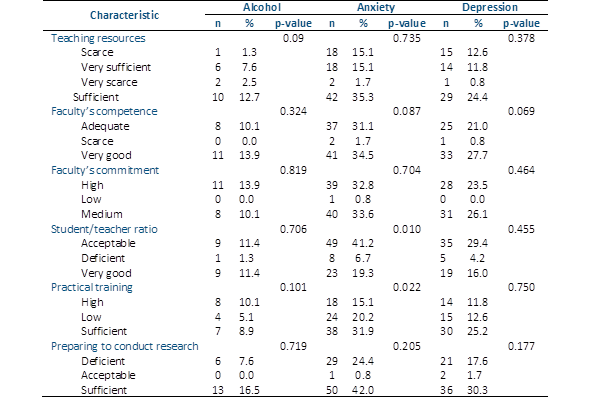

When asked about vocation and teaching resources, 53.8% of students reported that the teaching resources offered by the campus were sufficient, 52.9% thought that the preparation of faculty was adequate, and 50.4% believed that the general commitment of the faculty was high. Regarding student/teacher ratio, 54.6 % reported it was acceptable, 53.8 % thought that practical training was sufficient, and 67.2 % believed that they were prepared for research during their studies. The data are presented in detail in Table 2.

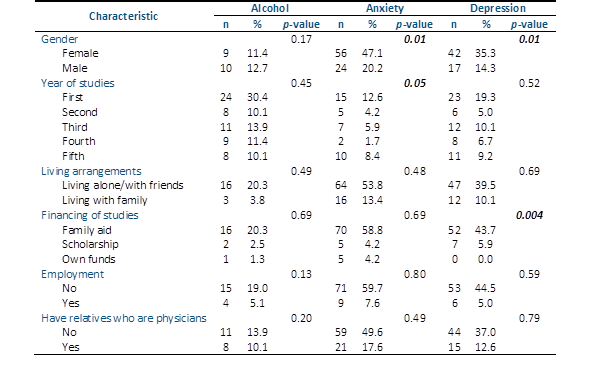

Students’ perceptions of their future professional activities were explored;51.3 % reported being interested in medical-surgical specialization, 28.6 % in medical specialization, 13.4 % in surgical specialization, and 6.7 % in diagnostic/laboratory specialization. In addition, 91.6% were interested in working in both public and private systems, only 5% in the public sector, and 3.4% in the private sector. Regarding the mental health of the surveyed students, 66.4 % reported consuming alcoholic beverages, of which 24.1 % recognized problematic alcohol consumption, according to the CAGE questionnaire. Of all the participants, 67.2 % reported anxiety according to the GAD-7 and 49.6 % reported depression according to the PHQ-2 (Table 3A).

Levels of anxiety and depression were significantly higher among female students: 47.1% (n=56) of them reported a mean score of 13.5 ± 5.08 at GAD-7 whereas 35.3% (n=42) reported 3.24 ± 1.84 at PHQ-2 screening for depression (all p≤ 0.01; Table 3A and Table 3B.

The rates of alcohol abuse and misuse did not differ among the sex groups. In addition, a higher number of students reported anxiety during the first year of training (12.6%; p=0.05), even if higher scores on the GAD-7 were registered among students in the third and fourth years of medical school (12.3 ± 5.15 and 13.6 ± 4.41, respectively; p=0,024). The rates and scores for depression were similar across the years of training.

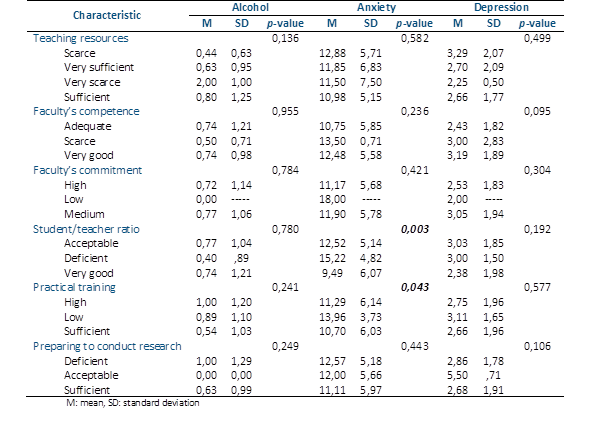

Depression scores were higher among students financed by family or scholarships (ranging from 2.82 to 3.52 on the PHQ-2 scale; p=0,048) even if 43.7% of depressed students were in the family financed sub-group (p=0.004). Interestingly, the rates of depression and alcohol abuse were not influenced by the perceived quality of medical training (Table 4A and Table 4B).

Nonetheless, scores of anxiety at GAD-7 were significantly higher among students perceiving students/teacher ratio as deficient or acceptable: deficient, 15.2 ± 4.82 > acceptable, 12.5 ± 5.14> very good, 9.49 ± 6.07 (p=0,003). Most anxiety symptoms were detected among those reporting that the student/teacher ratio was acceptable (41.2%; p=0.010). In addition, anxiety was higher among students reporting sufficient or low practical training during their medical education (31.9% and 20.2%, respectively; p=0.022), and students complaining of low practical training reported significantly higher scores on the GAD-7 than others (13.9 ± 3.73; p=0,043).

Discussion

This descriptive, cross-sectional, observational study conducted at the National University of Asuncion, Paraguay, aimed to report medical students’ perceptions of subjective well-being and the impact of medical training on their own mental health. It has been widely discussed that medical students may experience psychological distress in the course of their training for a number of reasons, including the transition from high school to university, parental expectations, matching personal expectations, financial and housing problems, difficulties in new relationships, amount of pressure, and work due to medical training, among others20. In addition, medical students are in a vulnerable age range where two-thirds of psychiatric disorders begin21.

In our sample, most of the medical students surveyed were female (59.7%), which is in line with trends registered worldwide in the last decade, as confirmed by the Higher Education Funding Council for England22. In fact, the number of women choosing a career in medicine has recently begun to rise, and 59.0% of students who accepted medical schools in 2017 in the UK were women22.

After entering school, medical students have to face new relationships and economic issues. In our sample, 78.2% of students lived alone or with new friends, even though 85.7% were financed by their family and had no personal economic resources. Leaving families and parental homes are key steps in the transition to adulthood and are frequently associated with starting university. Students at this stage may experience psychological distress in managing loneliness or new relationships as well as their economic resources, since most of them feel the weight of family support and investment23. The lifestyle of medical students away from their parental home may also be challenging and lead to unhealthy habits. In fact, Malatskey et al.24 have reported that medical students showed a significant reduction in quality of their lifestyle over time, with increased stress, weight gain, and fast-food consumption, and less exercise: in our sample 79.8% reported a sufficient amount of sleep (between five and seven hours), 56.3% dedicated between two and five hours to study, and only 36.1% were not engaged in any physical activity. These findings documented the average quality of lifestyle among the students surveyed. Regarding daily alcohol or stimulant consumption, 15.1% consumed stimulant beverages, and 58% regularly self-medicated. These findings may be compared to recent evidence from the international literature: a large study in the US reported that the percentage of medical students misusing stimulants may vary from 5.2% to 47.4%, and in most cases, misuse was due to academic enhancement (50-89%)25; in Italy, some recent evidence reported that 8.9% of medical students showed problems related to alcohol drinking, and 22.8% were admitted using stimulants (mostly cannabis and cocaine)26,27.

The use of cellphones and social networks among lifestyle and well-being issues revealed that 76.5% of students surveyed used their cellphones next to them during academic activity, and 99.2% regularly used social networks during the day. This topic may elicit a wider discussion, since the employment of cellphones, technology, and social networks is widespread among students and young adults, even for educational purposes. In 2016, Guraya28 published a large meta-analysis that concluded that 75% of medical students used social network websites, even if only 20% used these sites for educational activities. Avcı et al.29 reported that 93.4% of medical students used social media and 89.3% used social media for popularity, ethics, barrier, and innovativeness. The rate of social media employment in our study is similar to that reported in other surveys, but its impact on medical education should be further explored and discussed. Recently, Nisar et al.30 pointed out that social media may play a key role in enhancing educational settings and may negatively impact learning and academic performance because of distracting from the study and medical content. In particular during the COVID 19 pandemic, social networks and media have been useful for effective remote learning. To avoid a negative impact on medical students, criteria for choosing educational platforms, ethical guides, and professional standards should be discussed. For instance, in Paraguay, a previous survey on technostress among medical students reported that 47.4% of the participants perceived a low or moderate level of stress related to the use of technology, and technostress was significantly associated with levels of anxiety and depression17.

The quality of medical training and students’ subjective satisfaction are both relevant factors in terms of well-being and mental health. In our sample, 53.8% of students judged teaching resources as adequate and around 50% were satisfied with the general commitment of their faculty; 55% reported that the student/teacher ratio was acceptable, and 67% reported perceiving useful training in their educational course. These findings showed a good rate of satisfaction among students surveyed, even though rates of approval and satisfaction among students may greatly vary across different settings and institutions31. In addition, we explored the relationship between these satisfaction rates and mental health issues.

In our sample, 66.4% of students reported consuming alcoholic beverages, 24.1% reported problematic alcohol consumption, 67.2% reported anxiety, and 49.6% reported depression according to the rating scales employed. These ratings are particularly high when compared to previous reports: in Italy26, 8.6% of samples reported mental health issues while at medical school (including anxiety disorders > major depression > others) and 8.9% reported problems related to alcohol drinking; in Canada, 26% of students had been diagnosed with a mental health condition prior to medical school and 36% reported a current anxiety disorder, whereas 22% tested positive for CAGE with problematic alcohol misuse32. Similarly, in a recent report from Paraguay, 14% of students reported being followed by a mental health professional for specific conditions, including anxiety, and 20% tested positive for CAGE for alcohol abuse11. These comparisons may suggest that alcohol misuse ratings are similar across surveys, since the authors similarly employed the CAGE tool. Higher levels of anxiety and depression in the current study may be due to the subjective reporting of symptoms and interpretation of the instruments (GAD-7 and PHQ-2). Nonetheless, students’ perceptions of subjective wellbeing are relevant and should be properly considered. We explored the reasons for mental distress among sociodemographic factors and those related to medical education training. We found that student anxiety was significantly higher among those complaining of poor practical training during the educational course and an unacceptable student/teacher ratio. This evidence may confirm that the quality of training and student satisfaction are relevant factors that impact students’ mental health31. Anxiety scores were higher in the mid-last years of training, which may reflect the impact of students’ clinical engagement and their expectations for professional choices at the upcoming end of medical school. Levels of depression were not associated with the characteristics of training, but were significantly higher among students financed by families, probably reflecting students’ concern about families’ support, efforts, and their sense of commitment and gratitude23.

The limitations of this study include the small number of students surveyed, even if the sampling correctly met the sample size calculated; sampling from a university center only; the self-administered questionnaire and rating scales employed (even if all standardized and validated); levels of morbidity and students’ satisfaction may both reflect specific local social, health, and institutional characteristics in public health and university organizations.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that the mental health of medical students is a relevant issue in terms of public health and educational strategies. They face a challenging educational trail, and many factors may impact their subjective well-being, including perceived quality of training and university resources. In particular, students’ perceptions of lower quality of training and resources seemed to be associated with higher levels of anxiety in the survey. This suggests that educational policies and resources should be carefully revised and implemented to improve the impact of educational courses on students’ health and well-being.