INTRODUCTION

Cannabis is the most widely consumed illicit drug in the world1. It is mostly first experienced during adolescence, either as a peer integration factor or as a rite of passage2. The acceptance of cannabis by the world society, based on its medicinal use to treat nausea, pain or other ailments, was quickly followed by a desire to legalize the drug for recreational use3. The seemingly innocuous side effects helped open new avenues to make its trade legal4. Despite the expansion of its use, knowledge about its effects on human health is still limited5. On the other hand, the potentially detrimental impact on adolescent brain development remains a focal point for research, particularly because of the possibility that users in this age group may face an increased risk of psychosis6

Although the controversy over cannabis has already taken place in the past, it is now taking on different characteristics because of the new genetically modified high potency varieties7. For this reason, the current discussion is not comparable to earlier ones8. In the last two decades, the acceptance and significant increase in consumption worldwide have led to the development of policies in this regard9. In this sense, the debate has become politicized and polarized between different positions on its regulation or legalization. On the other hand, there are those who defend increased penalties, the continuation of the current prohibition, and even the persecution of users as well as dealers and distributors10.

In recent years, the complications of cannabis use have again attracted the attention of researchers, although they no longer focus on the cannabis-psychosis relationship as they once did11. Despite the existence of several indicators of increased use, there is still no evidence that fully proves the relationship between the first psychotic crisis or schizophrenia and cannabis use12. Despite this, it is now accepted and virtually established that the younger the age of onset of use, and the higher the potency of cannabis, the earlier the onset of psychosis13. Evidence shows that cannabis may be related to psychotic disorders, especially in regular users, in addition to potentiating symptoms in those already diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder14. Cannabis use has not yet been fully linked to the development of psychosis, although there is evidence of a cause-effect relationship, and a large number of articles establish some kind of statistical correspondence between its use and the first psychotic crisis15.

Considering that the legalization and/or decriminalization of cannabis could increase the frequency and quantity of its use, the present systematic review aims to summarize the findings of studies that investigated the risk, precocity, and intensity of psychosis in cannabis users.

METHODOLOGY

The PRISMA statement16 (minimum set of evidence-based elements to assist in the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses) was chosen as the methodological reference for the present systematic review.

Eligibility criteria

Clinical studies, comparative studies, data sets, legal cases, multicenter studies, observational studies, and twin studies, published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese, dealing with cannabis use and the development of psychosis or schizophrenia were included in this review. Excluded were animal studies, autobiographies, biographies, books, case reports, classic articles, clinical conference proceedings, commentaries, congress abstracts, dictionaries, editorials, historical articles, interactive tutorials, interviews, conferences, letters, meta-analyses, news, newspaper articles, patient education booklets, personal narratives, technical reports, audio and video media, and webcasts, studies of previously schizophrenic patients and unrelated affective psychoses, or articles that did not focus on only one aspect of the topic of interest, as well as studies without statistical information.

Sources of information

The search in PubMed and SciELO databases used the following terms: (marijuana OR marihuana OR cannabis OR THC OR tetrahydrocannabinol OR hashish OR pot) AND (psychotic OR psychosis OR schizo* OR delusional), in English, Spanish or Portuguese.

Literature search

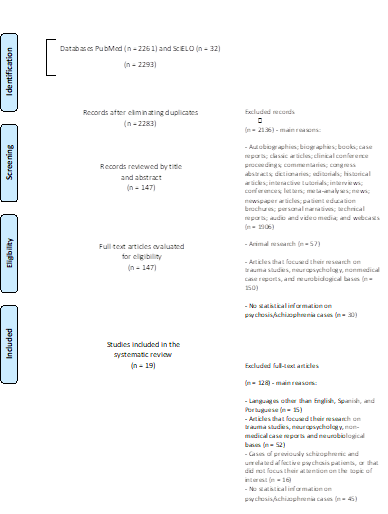

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for the identification, selection, eligibility, and inclusion of studies in the present systematic review, after using the PRISMA methodology16. A database search was performed by the first and last author (PASZ and JMCM, respectively) to identify relevant articles for the present review. The first search was completed in February 2018 and duplicate citations were removed from the various databases. A second search was conducted in December 2018, using the same terms and databases. A total of 2293 studies were identified.

Selection of studies

In the selection phase, the first (PASZ) and last author (JMCM) read the abstracts of all the studies found in the search (n = 2293), independently. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, and 1956 articles were excluded. Articles that were recommended for exclusion by only one of the two authors at this stage were further evaluated in a later phase. In the eligibility phase, the first (PASZ) and last (JMCM) author evaluated the full-text articles (n = 327), independently. The second author (GPB) made an inclusion or exclusion decision in cases of disagreement between the first (PASZ) and last (JMCM) author. Three hundred and eight articles were excluded based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Finally, 19 studies were included in the present systematic review.

Data collection process

The first (PASZ) and last (JMCM) authors read all 19 included studies independently. The first author (PASZ) tabulated the data from the studies.

Collected data

From the 19 included studies, the following data were collected: authors; year of publication; type of study; number of participants and mean age of participants; city, country, and time period in which the study was conducted; methodology; and main results. No method was conducted to combine the results of the studies due to the high heterogeneity of the studies: different types of studies; non-similar measures; heterogeneity of the intervention; and heterogeneity of sampling and design.

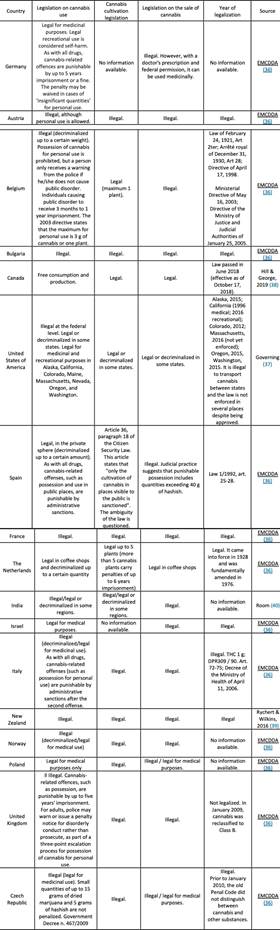

Cannabis legalization in countries

Taking into consideration the countries that had at least one study included in the present systematic review, the first (PASZ) and last (JMCM) author conducted a secondary review on cannabis legalization in those countries, looking for the following variables: country; legislation on cannabis use; legislation on cannabis cultivation; legislation on cannabis sale; year of legalization; source.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the studies

Table 1 shows the main results found in the present systematic review. Finally, 19 articles (17-35) were selected that possessed the necessary characteristics and dealt with the research topic in a sufficiently specific manner. All the studies were related to the use of cannabis prior to the first psychotic crisis and its evolution, varying the time studied and the characteristics of each study. Since the sample was varied, it is understood that cultural, legislative and temporal characteristics may have had a different influence in each case. Of the 19 articles included, 9 were comparative studies, 4 multicenter studies, 1 observational study, 1 randomized multivariate study, 3 longitudinal studies (of these, 1 was a prospective cohort, and 2 were prospective longitudinal studies), and 1 was a retrospective case-control study. Most of the studies were conducted in Europe (Netherlands, United Kingdom, Norway, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Poland, Czech Republic, France, Belgium, Bulgaria). Other articles came from the United States of America (New York, New Jersey), Canada, New Zealand, India, Australia and Israel. No studies were found from Latin America, the Caribbean or Africa.

Sample sizes ranged from less than 30 patients to more than 1500 in some cases, with the vast majority of studies containing between 100 and 800 patients. The focus was to study the relationship between cannabis use and the onset of psychotic symptoms. It should be noted that all the studies included women and that the mean age of the participants was between 17 and 35 years approximately (although in some studies there were patients under 16 years of age and even patients aged 78 years in others). The year in which the studies were conducted was between 1978 and 2015.

Main results

All the comparative studies analyzed, regardless of the size of the samples selected, related cannabis use to the first psychotic crisis. In the United Kingdom, cannabis was the most commonly used drug in the 30 days prior to the first psychotic crisis, although the result was equivalent in persons who had not used it17. Likewise, also in the United Kingdom, although not statistically significant, an increase in the specific use of cannabis in the first psychotic crisis was observed, mainly in the age group between 16 and 29 years of age, and mostly in female patients18. It has been reported that the link between cannabis use and the development of psychosis is specific, so it does not necessarily depend on the early presence of other psychopathologies to manifest itself19,20. Likewise, it is reaffirmed that cannabis use is a risk factor to be considered in health promotion19. When considering other factors throughout the individual's life (e.g., variations in socioeconomic status, age, treatment or not with antipsychotics), a study conducted in the United States of America22 has reported that cannabis use has been associated with an adverse course of psychotic symptoms and the evolution of schizophrenia.

In Spain, users who stopped using cannabis after the first psychotic crisis showed a better long-term functional outcome and fewer negative symptoms, compared to those who did not stop using23. In Canada, when studying and comparing (at the functional and somatic levels) adolescents in their first psychotic crisis with adults, similar results were observed. However, it is noted that adolescent cannabis users maintained positive and negative symptoms for a longer period, with lower predictions of access to paid employment and poor school performance24.

The multicenter studies analyzed showed the existence of an association between cannabis and psychosis, with a worse cognitive evolution25. In this regard, one of the studies (conducted in Norway) determined that cannabis use brings forward the onset of psychotic symptoms by three years, compared to non-user patients26. In Spain, a similar result was found in a comparative study27. In the United States of America, it was also found that pre-morbid use, in the five years prior to the crisis, was highly predictive of the onset of psychosis, increasing up to 2.2 times. These results were independent of sex and family history of the patients28. On the other hand, in Italy, another study did not associate consumption with a higher level of positive symptoms, although it was associated with less severe depressive symptoms. This study also suggested the role of cannabis as a causal factor in the activation of psychosis in certain vulnerable subjects, recommending that reducing its use may delay or prevent some cases of psychosis29. The 3 longitudinal studies also reaffirmed the association between consumption and psychotic symptoms19,30,31, in the United Kingdom and in New Zealand.

In an observational study conducted in the United Kingdom, it was found that patients who stopped using cannabis after the first psychotic crisis had fewer relapses, fewer hospitalizations and less need for medical care. On the contrary, those who continued with a high frequency of use, in this case Skunk-type marijuana, showed an unfavorable evolution with an increase in relapses, hospitalization time and the need for psychiatric care32. Studies in India found that cannabis users who were hospitalized for a psychotic crisis had a duration of symptoms twice that of non-users, and a higher probability of psychosis than users of other substances33. However, there were no significant differences when looking at all patients together in relation to their pre-morbid histories, family history of mental illness or personality type34.

Finally, in the United States of America, a multivariate randomized study attempted to characterize cannabis users with a first psychotic crisis. To this end, they were separated into two groups: those who were users and those who were not, and then compared. The results obtained showed that most of the patients who were users were male, younger than non-users, with an early onset of positive symptoms and lower socioeconomic status; they also presented lower school performance, as well as more severe hallucinations and delusions35.

Cannabis legislation in different countries

Table 2 shows the situation of legalization/decriminalization36-40 of cannabis in countries that had studies included in this systematic review. In this regard, considering these countries, it was possible to stratify them into 4 different levels of legalization/decriminalization of consumption. At the first level are countries in which cannabis use is totally illegal: Bulgaria, France, and the United Kingdom. At the second level, there are Israel and Poland, countries that only allow the medicinal use of cannabis. In the third level, which concentrates most of the countries included in this review, medicinal use is allowed and there is tolerance with personal use and/or in small quantities and/or in parts of the country. At this level are Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, India, Italy, Norway, the United States of America and the United States of America. Finally, Canada, Spain and the Netherlands are in the fourth level. In these countries the use of cannabis has been legalized/decriminalized more broadly. In this last level, Spain and the Netherlands stand out with a history of decriminalization/legalization of consumption that is much older than the rest of the countries.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this systematic review was to summarize the findings of studies that investigated the risk, precocity and intensity of psychosis in cannabis users in countries with different legislation regarding the legalization/decriminalization of this drug. Based on the 19 studies conducted in 18 different countries, it was verified that there is no data to support an increase in the earliness, risk, or intensity of psychosis in cannabis users in countries with a higher level of legalization/decriminalization of cannabis to date. However, it should be noted that several countries have still recent legislation about the recreational and/or free use of cannabis, in comparison with the legislation of the Netherlands or Spain.

In this sense, the studies by Ferdinand et al.21, in the Netherlands, González-Pinto et al.23 and Mané et al.27, both in Spain, present results influenced by legalization/decriminalization in those countries. However, in these studies, the findings of risk, precocity and intensity of psychosis among cannabis users do not present data that differ from the findings obtained in the other studies included in this review. With respect to the studies of the third level countries (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, India, Italy, Norway, United States of America and the Czech Republic), no discrepant data with the other levels were found either.

Nevertheless, it is possible to confirm that the relationship between cannabis use and the onset of psychotic symptoms is sufficiently substantiated. It should also be noted that the impact of cannabis-specific legislation on the health of the population should be evaluated longitudinally over the years. None of the articles makes specific reference to the legislative situation in the countries during the development of the research, nor how patients had access to cannabis. It was not possible to know what influence these factors had on the development of psychosis. Obviously, it cannot be overlooked that there are other factors that influence the development of psychosis, such as genetic, biochemical or environmental factors, and that THC is related to the increase of psychotic symptoms.

The present review had several limitations. First, only studies in English, Spanish and Portuguese were included. In addition, the included studies had different designs and measures of exposure and there were also sample differences. However, it was possible to perform a review with 19 studies, with a total of 7641 patients from various countries included. Pooling and analysis of the results of the different investigations was not performed, due to the heterogeneity of the included studies (e.g., different types of studies, non-similar measurements, very heterogeneous sampling and design). Future cross-national studies should be conducted with standardized measures to investigate what effect cannabis legalization/decriminalization has on cases in which psychosis develops. The present review does not intend to conclude with a statement about the potential effect of cannabis legalization/decriminalization on the incidence of psychosis cases but highlights the evidence.

In conclusion Cannabis use is associated with the development of psychosis. However, so far, there are no data showing an increase in the precocity, risk or intensity of psychosis in cannabis users due to the legalization or decriminalization of cannabis use. The absence of data to date does not exclude these possibilities, as none of the studies analyzed in this review specifically evaluated the effects of legalization/decriminalization policies on these outcomes. Therefore, prospective studies focusing on the effects of legalization or decriminalization policies should be conducted in countries such as Canada, Spain, the United States of America (some states), the Netherlands, and Uruguay.