1. INTRODUCTION: THE IMPORTANCE OF A CONFLICT-SOLVING INSTITUTION IN AN INTEGRATION PROCESS

It is well-known, that trade is the activity that generates the most litigation, consequently, for it to perform optimally, traders require a legal framework with clear and predictable rules, and a judicial apparatus they can trust in case of conflict. Otherwise, in the absence of these conditions, the market in question will be destined to fail. Therefore, it comes as no surprise, that integration processes, require some sort of dispute settlement regime, already since an early stage of their evolutionary paths.

The dispute settlement mechanism has always been contemplated as one of the fundamental ingredients of any integration process. Hence, even the most elementary and earliest integration agreements contain stipulations in this respect.

In any free trade area, innumerable offers, contracts, shipments, payments, receipts, etc., are carried out daily across the borders of the member states of the commercial group. Arbitration and national judicial systems are unable to solve the problems that the commercial activity of the integrated area might generate. This is so, for several reasons:

a) community law, unlike domestic or international judicial processes, poses specific problems. The lack of specialization of the courts of the member states, as well as international courts, significantly affects the quality of the communitarian case law. This ends up leading to a fragmented and not unified set of communitarian law;

b) the unequal application of these special legislation inevitably lead to differences in the interpretation of the supposedly single common legislation;

c) the ruling, becomes dependent on the national system of the country where it was issued, causing inconveniences when the execution of it, must be carried out in a different State;

d) there is a risk that the judge or arbitrator might mix nationalist favoritisms in his pronouncement.

The Southern Common Market (hereafter: Mercosur) was part of a project of open regionalism initiated in 1985, between Brazil and Argentina, aimed at promoting economic integration and political cooperation between its members. In 1991, its founders and current members: Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, signed the Treaty of Asunción, which created the mentioned regional trade bloc. Three years after that, the free trade agreement moved a step forward to establish the, up to date still incomplete, customs union,.

The idea of endowing Mercosur with judicial institutions was an idea that was present since the very beginning of the bloc existence, despite not having been dealt with in its foundational treaty. When the Treaty of Asunción was being negotiated, the intention of creating robust institutional mechanisms for settling disputes and enforcing agreements related to the regional bloc was already present in the minds of those in charge of shaping the project, largely influenced by the European experience. This early vision underscores the bloc's commitment to fostering a rule-based international order and promoting regional integration through effective legal cooperation.

In 1999, Prof. da Cruz Vilaça, former Judge of the European Court of Justice, remarked the importance of a strong jurisdictional institution, holding that:

“The Court of Justice of the European Community, composed of judges from all the member states, but entirely independent, has played a fundamental role in achieving the objectives of the Treaties and in consolidating the European Community as a community based on the rule of law. The Community Courts can be said to have ensured the legality of acts of the institutions, the uniform interpretation and application of the communitarian law in all member states, it also has protected fundamental rights in the Union area and acted as a driving force for integration by reminding member states of the commitments they made when they signed the Treaties and the objectives, they committed to achieve”.

The most conspicuous consequence of the deficiencies of the judicial system under Mercosur, is the extremely low number of claims filed before the judiciary authority of the bloc. The first of which was filed in 2005, long after the establishment of the region´s judiciary organ in 2002, and till the present, the number of total filed claims is still very low; less than 30 cases have been solved by Mercosur´s judicial organ. Consequently, the natural results are the lack of predictability and confidence in the system amongst trade actors, all of which hinders the successful development of the Union's intra- and extra-trade relations.

Awareness of these circumstances has led Mercosur's members to propose changes to make the regime more appealing. In this sense, during the negotiation of the region´s institutional framework that resulted in the Protocol of Ouro Preto, Argentina presented a project proposing for the establishment of a centralized high court, with mandatory jurisdiction and true enforcement power. However, the proposal was not accepted by Brazil, hindering the achievement of consensus in a block in which decisions must be made by absolute unanimity. Till the date, no satisfactory solution has been reached, and discussions have not moved beyond ineffective formulas.

2. THE PRELIMINARY RULING PROCEDURE VS. THE ADVISORY OPINION PROCEDURE

Across the globe, the incorporation of referral mechanisms has developed as a common practice among diverse integration movements. This is done so, with the purpose of unifying the interpretation and application of the rules of the integration system in question, all of what, fosters the progress of international structures made up of diverse participants.

The referral competence of any international court is motivated in certain common objectives, applicable to any integration scheme. Among these objectives are the harmonization and unification of legislation, the willingness of building legal certainty and the establishment of a mechanism for judicial cooperation between the international court in question and the national courts of the Member states. Thus, it is accurate to argue, that the referral tools represents a necessary element of regionalism.

The Preliminary Ruling of the European system (also sometimes referred as Preliminary Reference) and its counterpart, the Advisory Opinion of the Mercosur system, have been chosen as the object of comparison in the present work, due to the leading role played by the former in the regional integration process of its bloc. The ultimate aim is to compare the integration processes of both unions, through the evolution of these two judicial tools.

2.1. Preliminary Ruling of the ECJ

In order to talk about the institute of Preliminary Rulings of the European Union (hereafter: EU), it is essential to mention the institution behind it. The European Court of Justice (hereafter: ECJ) is the highest Court of the EU, and the highest guarantor of compliance, uniform interpretation and application of the union´s law in all the 27 member states, by preventing national laws from conflicting with EU´s law. The ECJ has the power to hear cases brought by any national organ of a member state with judicial competence, and its decisions are binding on all member states. Unlike any other regional court, when we refer to the European judiciary body, we are talking about a court of justice with a vast background of case law which has been shaping the existence of its bloc.

In line with this last, it is accurate to say that the ECJ is a one of the most powerful courts of the world, even compared to other international courts, it is still not possible to find other regional court with such a protagonist role in the integration process of its bloc. This statement is based on the fact that, many of the ECJ’s decisions resulted in paramount legal and institutional changes in the EU.

Regarding the topic of this section, the preliminary ruling procedure, it is not feasible to talk about the ECJ, without mentioning the crucial role that this referral tool has had in shaping the EU as we know it today. Therefore, it comes to no surprise that, Article 267 TFEU, is often regarded as the “Jewel in the Crown” of the ECJ´s jurisdiction. It was indeed, through the preliminary ruling that the ECJ developed ground concepts, such as “direct effect” and “supremacy of EU´s laws”. The authors, Mancini and Keeling, describe this very clearly with the following metaphor: “If the doctrines of direct effect and supremacy are, (…), the two pillars of the Community´s legal system, the reference procedure (…) must surely be the keystone in the edifice; without it, the roof would collapse and the two pillars would be left as a desolate ruin, evocative of the temple at Cape Sounion, beautiful but not of much practical utility”.

In the same sense, Voigt and Hornuf stated that: “…is the Preliminary Reference procedure that made the ECJ the powerful court it is today. (…) On its path to power, the court’s preliminary reference procedure played an important role, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Today, a majority of all cases brought to the ECJ draw on this procedure”.

Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in December 2009, the Preliminary Ruling procedure is regulated in Article 267 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereafter: TFEU). The ECJ has further regulated this referral competence in its statute (arts. 23 et seq.), its rules of procedure (arts. 103 et seq.), and also through its own jurisprudence. The material scope of this referral competence is expressly defined in Article 267, which establishes a twofold object for the request of a Preliminary Ruling: on the one hand, the interpretation of both, primary law (meaning the Treaties and Fundamental Rights Charter) and secondary law (meaning the laws adopted by EU institutions); and on the other hand, the determination of the validity of acts adopted by the EU bodies (secondary law).

In other words, this procedure is a tool available for national courts or tribunals to seek clarification and guidance from the ECJ on the interpretation and validity of EU law and the acts of its institutions, bodies, offices and agencies. The ECJ has the monopoly on the interpretation of European law, therefore, if a national court is unsure about how to apply EU law in a particular case, it can/should ask the ECJ for a preliminary ruling. The ECJ will then provide guidance to the national court, without ruling on the particular case.

Preliminary rulings are binding, that, means, that the national court that has referred the question to the ECJ must adopt the interpretation made by the European court when deciding the particular case. The obligation to follow the ECJ's ruling is not limited to the referring court, but extends to all national courts and authorities as well as to individuals and private parties of all the EU member states. However, it is important to note that the binding nature of preliminary rulings does not prevent national courts from referring new questions to the ECJ if they arise in similar cases, as this is necessary to ensure the consistent interpretation and application of EU law over time.

The preliminary ruling is the mechanism through which national courts and the ECJ have cooperated with each other for the uniform application of the EU law throughout the bloc´s territory. Moreover, it is also the basis through which these two judicial instances have engaged in discourse to determinate the appropriate extent of EU law when it conflicts with national legal norms.

There is a premise well established in the EU doctrine, which states that "the natural judge of the community law is the national judge". This means that, national judges, within a well-functioning integration process, become community judges in their daily work. This is because their decisions must ensure compliance with the communitarian law, even in cases of contradiction with the domestic law of their country.

2.2. Advisory Opinion of the Mercosur

The Permanent Tribunal of Revision of Mercosur (hereafter: TPR, according to its Spanish/Portuguese name) is the jurisdictional organ of the bloc. It has been created as a permanent tribunal for the settlement of disputes, by the Protocol of Olivos in 2002, and inaugurated in 2004, with the intention to "guarantee the correct interpretation, application and compliance with the fundamental instruments of the integration process and of the Mercosur's regulatory framework, in a consistent and systematic manner".

The Protocol of Olivos, granted referrals competences to the TPR, in addition to the traditional contentious ones. This competence, which allowed the TPR to further contribute to the integration process, is known as the advisory opinion. These opinions consists on substantiated non-binding pronouncement of the TPR on questions regarding the interpretation and application of Mercosur legislation, with the aim of safeguarding its uniform interpretation and application in the territory of the member states. The regulation of advisory opinions was done by the Counsel of the Common Market (hereinafter: CMC), through its Decision 37/03. This regulation was in force for almost 20 years, until it was replaced by the decision 05/22 in July 2022.

The parties entitled to request such opinions from the TPR are: the member states (as a whole), the Mercosur decision-making bodies, the High Courts of Justice of the member states and the Mercosur Parliament. When a request for an advisory opinion has been filed, the TPR must assess its admissibility; once the request has been admitted, the TPR has 65 days to issue a response. This pronouncement will provide guidance to the national court or authority that requested it. However, the requesting party is not bound by the TPR's ruling, thought it would very probably take the opinion into consideration when deciding the case.

In this process, the TPR acts in plenary sessions, being convened each time a request is filed, given that it does not operate on a permanent basis. For the purpose of issuing advisory opinions, the TPR operates through the exchange of remote communications. The expenses generated by the exercise of this referral competence, should be borne by the requesting party, this means that, it could be covered by the regional budget itself (when it is requested by Mercosur institutions) or by the member states´ budget (when it is requested by a national supreme court, or by a member states).

2.3. Comparative analysis between both judicial tools

It is easy to identify, some very clear differences between the two referral institutes in terms of: their binding nature, the legitimacy to request them, their legal basis, their material scope of application, the time frame to deliver a pronouncement and the popularity and real scale of contribution of each tool to their respective integrated judicial system.

The binding nature is probably the most notorious difference between the ECJ's preliminary ruling and the TPR's advisory opinion. Whereas both allow national courts and other authorities (in the case of Mercosur) to seek guidance from a higher regional court on the interpretation and validity of integrated law and institutional acts, the ECJ's rulings are binding, while the TPR's ones are, as the same name says it, just an advice, therefore, not binding upon the requesting party. The decisions of the ECJ have the force of res judicata, meaning they are binding, not only for the particular case for which the Preliminary Ruling has been requested, but also for the rest of countries in the union, which must apply the principles outlined in the ruling each time they are faced with a case of the same characteristics.

The second most important difference is given by the legal nature from which both acting bodies derive their legitimacy. This point might allow us to understand the reason of the previous difference spotted. While the EU institutions have been created upon the rule of supranationalism and the four principles of communitarian law (autonomy, primacy, direct effect, and responsibility of the State), the legal nature of Mercosur´s institutions is intergovernmental. This explains not just the difference in the binding nature between our two judicial tools, but also, in more broader terms, a core distinction between the EU and the Mercosur.

In connection with the above, Dr. José Antonio Moreno Ruffinelli and Dr. Joao Grandino Rodas, designated arbitrators of the TPR to rule in the first requested advisory opinion (CO 1/2007), have expressed in relation to the purpose of the institute under study that "Advisory opinions, although they are not binding for the national judge, constitute a formidable instrument of harmonization, thus effectively contributing to the aim of supranationality that should be an aspiration of any integration process...". These arbitrators have understood that another purpose of the advisory opinion is to promote a supranational organization through a profound jurisdictional commitment to the interpretative task and the institutional progress of the bloc. We will come back to this later.

As per the legitimacy to request it, the European tool can be requested by all national organs with jurisdictional competences, regardless of whether they are of first, second or last instance; whereas Mercosur´s tool can only be requested by last instance national courts. Additionally, and in opposition to the European case, the advisory opinion can be requested by the Mercosur´s three decision-making bodies (the Common Market Council, the Common Market Group and the Trade Commission), by the Mercosur Parliament (known as “Parlasur”), and by member states acting jointly. This last requisite, prevents states from making an individual request for an advisory opinion, constituting another example of the intergovernmental dynamic that leads the Mercosur´s integration process. In other words, it will only be possible to access the referral mechanism through the consensus of all member states, this means that, an agreement (in terms of requesting the advisory opinion and its content) between the executive authorities of each member state is necessary for it to proceed.

This circumstance only confirms the traditional position of Mercosur's member states, which have always shown strong resistance to lose control over Mercosur´s operations, as well as to create independent and supranational institutions, capable of acting autonomously from the national governments.

Beyond the subjective legitimacy to access the referral mechanisms, it is relevant to mention that, under the European system, the preliminary ruling can be an optional or a mandatory tool. It is optional for all national courts or tribunals, except for those against whose decisions there is no judicial remedy under national law. In this last case, requiring a preliminary ruling, when an EU legislation/acts are concerned in the particular case, is mandatory. Last instance courts, must seek clarification, when this is necessary to deliver a lawful final decision. On the contrary, the advisory opinion is always an optional tool for all the parties allowed to request it.

In relation to the scope of application of both institutes, their use could be done to refer matters of interpretation of primary law and matters of interpretation, and also validity, of derived law; all of which reaffirms the common purpose analyzed above, oriented to avoid dissimilar interpretations within the integrated area, that may jeopardize the integration process.

In relation to time limits to deliver a pronouncement, the TPR has a deadline, established in its regulation, for issuing advisory opinions. Once the admissibility of the request has been approved, the TPR has 65 days to deliver its Opinion. The ECJ does not have any fixed deadline established by explicit regulation, however, in average, decisions are delivered after 12 to 18 months. Nonetheless, it exists an urgent procedure under the ECJ system, regulated in paragraph 4 of Article 267 TFEU, only available for cases when a person´s liberty is at stake.

As per what regards the solicitation process, both blocs had established a quite similar process. In both cases, the requesting subject must submit a written request, following its internal procedures. The written submission must include a description of the case and the matter of law for which a clarification is needed; the request must also explain and support the reasons why the applicant believes that a consultation should be submitted. Once the request has been filed, the ECJ and the TPR, respectably, will decide upon the admissibility of it, based on whether the request for clarification is sufficiently justified, whether the matter of consultation has already been solved in the past, etc. Both institutions may request additional clarifications and documentation from the applicants before deciding upon the admissibility. It must be emphasized that the purpose of these referral competences is not to obtain pronouncements over substantive issues in litigation proceedings, or to interpret domestic law. In both scenarios, the filing of a referral request by a jurisdictional organ, causes the suspension of the main litigation process, till the TPR or the ECJ, as the case may be, delivers its clarifying pronouncement.

Is common for the ECJ to hold hearings to allow the parties to present their arguments in person, whereas this possibility doesn´t exist under the TPR system. The TPR is convened for the sole purpose of issuing the requested advisory opinion, and most of the deliberations are conducted remotely, in opposition to its European counterpart, which conducts its deliberations in person in its premises in Luxemburg. In the case of the ECJ, the judges are magistrates elected for fixed terms of 6 years, with possibility of renewal; they are servants of the EU with a stable appointment.

In terms of the ruling itself, preliminary rulings of the ECJ typically do not contain the individual votes or positions of the judges, while on the contrary, advisory opinions of the TPR contain the arguments and votes of each individual arbitral judge. The ECJ operates on the principle of collegiality, which means that the judges deliberate and reach a collective decision. When delivering judgments, the court provides a single interpretation of EU law without revealing the internal deliberations or attributing individual positions or votes to individual judges. This approach is intended to emphasize the unity and coherence of EU law and to ensure that the ECJ’s decisions are seen as the court's decision rather than the opinions of individual judges. The focus is on the legal reasoning and the interpretation of EU law rather than the internal dynamics of the court's decision-making process. Despite the differences just spotted, both judicial institutions make their decisions publicly available.

Another point of differentiation worth mentioning is the popularity of these tools in their respective regional blocs. The ECJ has deliver more than 13.000 preliminary rulings since its creation. This illustrates the utility and contribution of this tool in the integration process of its bloc. The opposite is the case in its South American counterpart, which till today, has issued only 3 advisory. While the European procedure has shown an increase of its utilization over time, the South American one has experienced a decrease, to the point that no advisory opinion has been filed during the last decade.

Lastly, divergences exist related to the payment of the expenses required for the activation of these referral mechanisms in each regional bloc. In the case of Mercosur, when the request of an advisory opinion is done by the High Courts of Justice of a member state, the costs associated with the issuance of an advisory opinion (expenses and fees of the TPR´s arbitrators) must be borne by the member state to which the requiring Court belongs. The economic burden that the referral process entails for member states has a negative impact on the use and promotion of this tool, causing at the end, a detriment against the harmonization progress to which the TPR can extensively contribute through the exercise of its referral competence. In the end, the tribunal's interpretation benefits the integration process, and not only the body that requested the advisory opinion, which is why this distribution of costs is often considered unfair and disadvantageous to Mercosur's overall progress and advancement.

Dr. Fernandez de Brix, when acting as rapporteur of the first advisory opinion issued by the TPR, stated that, the fact that the referring state is responsible for the payment of the expenses incurred in during the referral process:

"…does not guarantee a mechanism that ensures participation, since this will undoubtedly discourage the advisory opinions (…) article 11 is discriminatory in relation to the form of payment of the consultation, that might vary depending on whether it comes from the Mercosur bodies, the member states or the Supreme Courts of Justice. This violates the nature and purpose of the advisory opinion, resulting in a clear and categorical violation of the Protocol of Olivos". He then concluded in this respect by saying "it is discriminatory because the advisory opinions have the aim to unify the interpretation and application of the Mercosur´s integration laws; if only the state of the consulting Court pays, it brings a free benefit for the other member states. In other words, the state that makes the effort for the institutional and legal consolidation of Mercosur, pays for all the others".

Conversely, the preliminary ruling procedure is covered by the EU´s budget, this means that, the requiring national court would not have no pay anything, encouraging the usage of this tool, instead of creating barriers to its access.

At this point, it is necessary to come back to the binding and mandatory nature of the advisory opinions and bring up a current debate around it. Some scholars believe that the interpretations of the TPR, issued in response to a referral request, should be considered binding, meaning that, the body that has referred the consultation, must proceed in accordance with the decision of the highest jurisdictional body of Mercosur, without the possibility of disengaging from it. This position is based on the idea that the TPR is the highest jurisdictional body of Mercosur, and its decisions carry significant weight.

The legal scholars that argue in favor of this approach, base their argument on the fact that the regulation of the Protocol of Olivos for the Settlement of Disputes in the Mercosur (done through the aforementioned CMC Decision 37/03, replaced in 2022 by the CMC Decision 05/22 ), states clearly and categorically in its Art. 12, that advisory opinions issued by the TPR won’t be binding or mandatory. It is possible to argue here, that this regulation made by the CMC, is an act of derivate/secondary law, that goes against primary law of higher hierarchy. Specifically speaking, this regulation goes against the provisions of the Preamble of the Protocol of Olivos, which states the following:

"The Argentine Republic, the Federative Republic of Brazil, the Republic of Paraguay and the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, hereinafter referred to as "States Parties";

TAKING INTO ACCOUNT the Treaty of Asuncion, the Protocol of Brasilia and the Protocol of Ouro Preto;

RECOGNIZING

That the evolution of the integration process within the scope of MERCOSUR requires the improvement of the dispute settlement system;

CONSIDERING

The need to guarantee the correct interpretation, application and compliance with the fundamental instruments of the integration process and the normative set of MERCOSUR, in a consistent and systematic manner;

CONVINCED

Of the convenience of making specific modifications to the dispute settlement system in order to consolidate legal certainty within the scope of MERCOSUR;

HAVE AGREED as follows: (…) "

(highlights belong to the autor)

As can be seen in the extract transcribed herein, member states have recognized here the necessity of fostering the evolution of the integration process in Mercosur, and the consequent urge to improve the bloc's dispute settlement mechanisms, together with the imperative need to guarantee a uniform interpretation and application of the integration laws in order to provide the integration process with the necessary legal certainty.

Consequently, it is possible to conclude that the CMC, when regulating this procedure, should have taken into account the objectives of the member states, expressed in the primary law of the bloc. Making the advisory opinions binding and obligatory would have contributed to achieve the uniform application of Mercosur’s laws, and make the bloc meet its goals. Therefore, it is possible to ask ourselves, with good reasons, whether Art. 12 would not be contradictory to the objectives of the referral tool, as stated in the Protocol it regulates (primary law) of the bloc.

In this sense, the doctrine that adheres to this position, believes that the advisory opinions should be deemed binding and mandatory by the requesting party, ignoring the opposite nature that was established by the regulation of the CMC.

However, it should be kept in mind that, if the reader were to opt for this interpretation, in the sense of the binding and obligatory nature of the advisory opinions, other peripheral issues might arise. The enforceability of these pronouncements should also be contemplated, for the case a member state decides not to comply with it; the binding nature would not play much of a role without a coercive mechanism in place. Currently, the questions regarding what legal mechanisms are available to enforce the decisions of the TPR, and whether the TPR should have the power to issue sanctions or take other measures to ensure compliance, are topics that have not yet been dealt with. All these unresolved matters constitute a significant obstacle in favor of this posture.

Accordingly, although some may be in favor of this interpretative position, given the current state of the situation: a lack of clear and consistent regulations and a lack of coercive mechanisms in the case of possible non-compliance (due to the intergovernmental nature that characterizes the Mercosur process), it is difficult to believe that the application of this interpretation would lead to satisfactory results.

On the contrary, the EU, given its supranational structure, has a system of coercive measures in place to ensure compliance with preliminary rulings issued by the ECJ. When a member state is found to be in breach, the ECJ issues a warning, requiring the state in question to take certain actions to comply with the ruling in a given period of time. If the member state, still fails to comply with the ruling, the EU can use a number of coercive measures to ensure compliance.

These measures consist of suspending certain benefits or rights of the member state, such as voting rights or access to EU funding, or taking legal action against the member state concerned, in order to ensure compliance with the preliminary ruling.

Mercosur does not have the same coercive measures as the EU to enforce compliance with its rulings. The South American system is designed to address disputes and non-compliance through negotiation, consultation, and dispute settlement mechanisms, rather than through coercive measures. The enforcement of any ruling coming from a Mercosur authority, ultimately falls on the member states themselves, and there is no specific mechanism for imposing penalties or other coercive measures on a non-compliant member state.

Given this context, political and economic pressure among countries can play an important role in dissuading non-complying members from continuing their behavior of breach. However, it is worth noting that this mechanism is not only used in justified cases of breach, but is also often used in an abusive manner by powerful countries to get others to do or not to do a certain action, depending on the interests of the powerful country exerting the political/economic pressure. Therefore, this technique often leads to unfair results and undermines the principle of equality among member states, which is one of the essential pillars over which an integration process should be built. This situation has occurred on many occasions in the framework of Mercosur, where the larger countries, especially Brazil, have taken advantage of their favorable position to breach Mercosur rules without suffering any consequences, or to easily manipulate the actions of other countries of the bloc in their favor.

3. POLITICAL, HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL CONTEXT UNDERLYING THE MERCOSUR´S DESPAIR EVOLUTIONARY PROCESS - COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS VIS-À-VIS THE EU

In this section we will examine how the evolution of a regional integration process is reflected in its institutions. In the analysis of regional integration processes regional institutions have an important position both as by-products of integration and as agents of integration, whose role and actions affect the whole process.

Regions can be defined as groups of contiguous territories linked by a degree of interdependence with possibility of cooperation. In this sense, 'regional integration' is commonly defined in a broad way as: institutionalized cross-border cooperation.

Last years have shown asymmetric developments of different regional blocs, causing uncertainty about a positive future of many integration processes. However, the regionalist trend is growing, with countries around the world seeking to form economic, social and cultural blocs. This tendency is reasonable, given the benefits it entails: countries can grow stronger by working together on political and economic fronts, and build mutually beneficial relationships that promote peace, stability, and prosperity for them all.

After 32 years from its creation, Mercosur, being the fifth biggest economy of the world, has shown itself as an actor with the potential to have a leading role in international trade relations, if set-up in the right way. For certain unique features, Mercosur is sometimes considered as the world’s second most integrated multilateral regional group after the EU.

As Professor Mukhametdinov, specialist in comparative regional studies, believes, there are several grounds for a valid comparison of Mercosur with the EU. Both blocs have expressed commitment to a common market and have undertaken measures for its implementation. Also, both have acquired international personality with the ability to participate in international agreements. On the surface, the two blocs appear to have parallel institutional systems: every major EU institution has an analogue in Mercosur. In terms of the economic process, both blocs confirm the traditional sequence of economic integration, that goes from a free trade agreement to a customs union and finally to a common market. However, Mercosur never reached this last stage, getting stuck halfway from achieving the custom union.

Regarding the most notable differences, we can mention the following:

Mercosur is a more recent process than the EU; it was founded in 1991 while the EEC has operated since 1957.

Mercosur has fewer Member states, 4 versus 27 in the EU.

There are 24 official languages in the EU and only 3 in Mercosur, entailing a great difference in the degree of cultural diversity between the two blocs. When it comes to working languages, the Mercosur has 2 (Spanish and Portuguese) and the EU has 3 (English, French and German).

In connection to the previous point, Mercosur is much more culturally homogenous, while the EU encompasses a much broader cultural diversity.

The degree of commercial interdependence within the EU is 10 to 15 that of Mercosur.The EU has been successful in the facilitation of intra-regional economic exchange through the establishment of a single currency among the majority of its members.

Differences in the geopolitical motivations for the creation of the two blocs can also be spotted. These are most prominently characterized by the different nature and impact of the US policy in relation to the two regions, and by consequences of World War 2 in Europe and the lack of a security dilemma in the Southern Cone prior to the formation of the blocs.

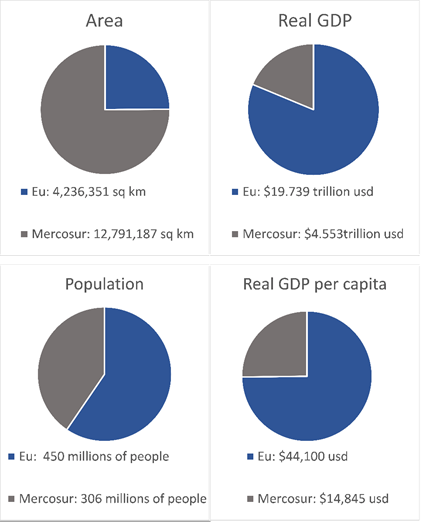

As we can see in the charts below, Mercosur’s basic indicators differ substantially from those of the EU. This will help the reader to be better contextualized, and consequently better understand what is here described.

Source: The information source for the elaboration of these charts has been obtained from: The World Factbook. www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook. Accessed on the 15th of March 2023.

As stressed before, the legal nature of the intra-members´ relations in the Southern cone differs from the European one. Mercosur’s strictly intergovernmental dynamic has often been held accountable for the slow pace of integration, including the failure to achieve a common market. All decisions require consensus among the member states, this means that, Mercosur is restricted to advance only those measures of integration that have been agreed upon by all member states. Mercosur’s decision-making institutions consist of representatives of the member states’ governments; the decision-making institutions do not operate on a permanent basis, but meet periodically and produce decisions through intergovernmental mechanisms that always require unanimity. On the contrary, EU´s institutions operate on a permanent basis and take decision under a supranational mechanism by consensus, absolute majority or qualified majority depending on the matter.

This is explained by the political trend that prevails not only in South America, but in all Latin America. Presidentialism has often been associated with instability, corruption, and authoritarianism. This is because it often leads to a concentration of power in the figure of the president, causing a lack of checks and balances, and a tendency towards authoritarianism. Additionally, presidentialism often involves a winner-takes-all system, which can exacerbate political polarization and prevent the emergence of a robust opposition. It does not involve bargaining among several players since one of them, the president, overrules all others, be they cabinet ministers, congressional majorities, the diplomatic corps, or regional institutions. For all these, many presidents in the region have been accused of abusing their power and suppressing political opposition.

Another relevant characteristic of presidentialism in Latin America is the tendency towards a "personalistic" style of leadership. Presidents in the region often cultivate a cult of personality around themselves, which often translates into a lack of institutionalization and an overreliance on individual leaders rather than democratic institutions. The external politics of these countries change substantially from one president to the other, creating great instability and difficulties in any long-term commitment, such as the one these countries have assumed when creating Mercosur. It is not surprising, therefore, that Mercosur, after 32 years of existence, has not yet managed to overcome its intergovernmental structure.

Member states have repeatedly violated their obligations towards their Union, not only due to the difficulties in implementing solid long-term international policies, for the reasons mentioned above, but also possibly motivated by a lack of consequences and a loss of faith in their bloc.

Firstly, Mercosur’s integration was driven by political objectives shared between Argentina and Brazil, aimed to improve their relationship through regional integration in order to ensure security and democracy in South America after rather tense relations between both countries during the 1970s. Secondly, Mercosur was part of a new economic development strategy of its members, to increasingly open their markets to the world. The project was successful throughout the early 90s, years in which Mercosur grew at an accelerated rate. Intraregional and extra-regional trade and investment increased so that regional integration was a win-win situation for all members. Between 1991 and 1998 intra-regional trade quadrupled, and the bloc´s extra-regional trade duplicated. But at the end of the decade, after several economic crisis and political instability in the region, the Union´s evolution pace started to slow down, and unresolved differences between member states raised doubts about the future viability of the Union. As Professor Malamud says, the group "entered a pattern of cyclical crises and rebounds that have defined it".

It may come as a surprise that Mercosur´s integration is moving slower than expected, especially given certain attributes of the South American case, in comparison with the EU. For instance, there are fewer cultural obstacles, fewer member states, what means, fewer participants with whom to negotiate for decision making, and the more globalized economy at the time of Mercosur´s creation, than in the years of the European Community formation.

Heavy economic imbalances and reliance on extra-regional economic relations caused Mercosur to become increasingly fragmented, which culminated in bilateral agreements, between Mercosur Member State and a third country, in flagrant violation of the Union´s rules and the compromises assumed. This is the case of the bilateral economic alliances between Uruguay and China and Brazil and the EU.

Many authors explain Mercosur´s slow development on the series of never-ending economic crises that keep affecting its underdeveloped countries, and the lack of political will, especially from the side of Brazil, to pay the costs of genuine integration.

3.1. Asymmetry of power among mercosur members - internal dynamics

Mercosur's failures are increasingly perceived as a consequence of its institutional fragility and the serious macroeconomic asymmetry between Brazil and the rest of the countries in the bloc. Brazil is by far the region’s most important country in economic and political terms, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay are far behind. The Brazilian ambiguous position towards the South American Common Market, is worth noting.

Brazil is the central power of the region, not just base on its economic dominance, but also other indicators, such as territory and population, point to Brazil’s central position in Mercosur. Today, Brazil’s population accounts for the 72% per cent of the region’s total population and the country contributes to the 74% per cent to Union’s gross domestic product (GDP). Brazil’s geographical area is more than twice that of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay together. At the same time, Brazil is the one-member state of Mercosur for which extra-regional economic relations are most important. Most of Brazil’s exports are addressed to the EU and the United States of America, its regional neighbours come far behind this two. Given Brazil’s dominance in South America, its behaviuor was decisive for regional cooperation within Mercosur.

Brazil’s motivations towards the Mercosur had been very volatile, throughout Mercosur´s history. The behaviour of the region biggest economy towards the bloc, shifted from cooperation during the 1990s to noncollaboration and even violation of Mercosur´s laws. During the early 1990s, Brazil actively pushed cooperation and led the establishment of the Union, seeking to increase its global presence, boost its international bargaining power, access extra-regional markets and attract investment. For the smaller member states, Paraguay and Uruguay, Mercosur was a vehicle to teamed up with their bigger neighbours in order to make their tiny markets visible on the global market. The smaller Member states and Brazil differed over the actual form of Mercosur´s institutional setup. The first ones favored supranational institutions and the delegation of competencies to decision-making bodies, while the second one, preferred Mercosur to be a union of nations, where decisions had to be taken by consensus. In the end, the institutional structure adopted was in line with Brazil’s position. All decision-making institutions operate under an intergovernmental dynamic and decide by unanimity.

The early 1990s were a big success for Mercosur, generating a large intra-regional market and attracting extra-regional investments and trade. However, years of growth ended with global crises that hit the region. This last led to a competition among the bloc´s Member states, for declining extra-regional investment. In 1999, in a sort of "every man for himself", Brazil decided, unilaterally, to devaluated its currency, in order to get a competitive advantage in comparison to its smaller neighbours. Brazil did nothing to inform the other countries of the bloc, and rejected any type of monetary coordination. Consequently, Brazil´s economy recover quickly, improving its international economic competitiveness at the cost of its neighbours. Unable to compete with its bigger neighbor, Argentina entered a deep recession that resulted in one of the history’s largest defaults, while Brazil’s economy recovered quickly. This caused increasing tensions among the Member states, what resulted in fragmentation and stagnation of regional integration in Mercosur, which thus far, has not yet regained the dynamic it had during the 1990s.

Due to this deadlock, Brazil started looking for international cooperation outside of the regional organization, by pushing the establishment of UNASUR, which, though not incompatible with Mercosur, nevertheless indicated a loss of faith in the Mercosur project. Even more critically, Brazil put the bloc´s extra-regional trade negotiations with the EU temporarily on pause, and in the meanwhile, launched its own bilateral partnership with the EU, what is in clear violation of Mercosur´s laws. However, it should be acknowledged that the interest in regional cooperation also declined in Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay due to a lack of confidence and positive vision towards the integration process.

In the end, although historically Brazil has been very much against the Bolivarian dream of unifying the South American continent, today it has become an essential and indispensable actor in any integration project. Brazil’s priority has always been trade, while interregional institutions have only limited interest for the South American power. Cooperation may be relevant for the smaller Mercosur members. Brazil’s strategy in the negotiations has been offensive in the economic dimension and defensive in the political dimension.

4. CONCLUSIONS

The preliminary reference procedure has been and, without doubt, will continue to be an important instrument of European integration. Unfortunately, we cannot say the same of its South American par. As Mercosur continues to evolve and face new challenges, the need for clarity and guidance on legal matters will only increase, making advisory opinions a valuable tool for resolving disputes and promoting legal certainty in the region.

Although created under the influence of the successful European case, and intended to achieve similar results, Mercosur’s advisory opinion has yet not achieved the aims of its creation. This issue is not an isolated case, but rather part of a set of fundamental weaknesses in the Mercosur system that had existed since the block's foundation, and which have not been remedied over time.

Despite their differences, both the ECJ and TPR have played a role, to different extents, in strengthening the rule of law and promoting legal certainty within their respective legal systems. As regional integration and cooperation continue to evolve, it is important to consider the experiences of these two institutions to identify best practices and opportunities for further collaboration in the pursuit of a more harmonized and effective legal order.

It is essential for economic integration processes, that the rules governing them are interpreted uniformly in all different national jurisdictions. This way, the laws applicable to situations arising from the integration process produce the same effect in all the bloc´s territory. Achieving a uniform interpretation, through a binding system of advisory opinions, would ensure that Mercosur regulations have the same scope and application in all Member states.

The reduced operability of Mercosur's judicial system, when compared to the European model, shows that institutional weakness is not just an abstract concern, it is a problem that requires political will, and a real commitment of its member states. The issue has to be put on the political agendas of the member states and dealt with the preeminence it requires, if the Mercosur project is to move forward feasibly.

A common market can hardly become a reality if economic actors and citizens are not allowed to protect their interests. When the integration process still weak and does not yet have the necessary civil legitimacy, the role of the judiciary system results significantly important to accelerate the integration process and consolidate legal certainty in order to gain the necessary confidence of the civilian population in the process. When the EC political process was paralyzed, in the 1960s and 1970s, ‘Judicial activism’ of the ECJ served as the driving force to European integration. Without it, the integration efforts would not have been as profound and sustainable.

Despite parallel institutional framework between Mercosur and the EU, there is a significant variation between the forms of regional institutions and the ways they operate. The lack of supranational prerogatives restricts the autonomy of the bloc and the ability of decision-making bodies to act as an impartial intermediary among the Member states, that would place the common interest of the integrated area above interests of its members. The TPR’s failure to become the absolute superior authority of Mercosur law, the whole system lacks the centralization that is crucial for the legal certainty that any legal community requires. Therefore, the TPR is just a compromise between the desire for a firmer legal system and forces resisting supranationality.

Mercosur weaknesses are increasingly perceived as a consequence of its institutional fragility and the serious macroeconomic asymmetry between Brazil and the rest of the countries conforming the bloc. Many of the causes of the slow pace of Mercosur's evolution are due to structural, internal issues, which are complex to change in the short term. Nevertheless, in the area of dispute settlement, we can suggest certain changes in order to build a strong judicial authority, with real power, that collaborates in achiveing the legislative harmonization of the bloc, and is capable of being a true agent of integration. For instance:

Make the advisory opinion an effective and useful tool, by broadening the legitimacy to request it, bearing the costs of the procedure through the Mercosur´s budget and rethink the legal effects of the Advisory Opinions in order to make it obligatory and binding, through clear and coherent rules. The final purpose of the Advisory Opinion is to guarantee the uniform application of Mercosur law; therefore, it can be said that, there is no reason for keeping this ruling as not-binding.

Strengthen the conflict settlement system by making the TPR a permanent and stable jurisdictional court; appointing a permanent number of independent judges who, through their rulings, will gradually generate jurisprudence on regional integration matters.

To move towards a supranational dynamic, for which the Member states must gradually, but effectively, delegate sovereign powers and competencies to the institutions of the Mercosur bloc. In this way, Mercosur would count with an effective system of coercion to correct possible deviations of the Member states in complying with their obligations to the bloc.

The success of any regional integration project requires a well-designed institutional framework that is capable of ensuring the fair representation of its member states, promoting cooperation, and guaranteeing effective decision-making processes. However, despite its potential, Mercosur has been facing numerous challenges and limitations that have hindered its progress and effectiveness as a regional organization.

Concentration of power has made it difficult for Mercosur to achieve the necessary levels of consensus and cooperation required for effective decision-making and implementation of regional policies. The lack of effective checks and balances has created an environment where leaders can prioritize their individual interests over the common good of the region. This has led to instances where Mercosur member states have failed to meet their obligations under the treaty or have pursued their own economic and political agendas at the expense of other members.

In addition, the presidentialism model has resulted in a significant power imbalance between the larger and smaller member states, with the former often dominating decision-making processes and leaving the latter with little to no influence. This has led to increased tension and mistrust between member states, further undermining the integration process.

In contrast, more successful regional integration projects such as the EU have adopted a more balanced and democratic model of governance, where power is shared among different political actors, and decision-making is guided by the principles of transparency, accountability, and cooperation. This has allowed the EU to overcome national interests and achieve a high level of integration and cooperation between its member states.

Redesigning the tools of Mercosur law, putting them into practice, subjecting them to a careful but creative use, can invigorate legal aspects that need to be reviewed in order to strengthen the southern bloc and take it to a new step in its development.