INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a global public health problem, with high prevalence rates and rapid growth at all ages, resulting from a positive imbalance between intake and energy expenditure. Despite being modifiable risk factors, overweight and obesity remain a global public health problem. The prevalence of obesity has doubled since 1980, with more than 1.9 billion and 39% overweight adults. By 2025, global obesity is estimated to reach 18% in men and exceed 21%. In Latin America, an estimated 58% of the population (about 360 million people) are overweight and 23% (140 million) obese. Also, 50% of men and 60% of women are expected to be overweight or obese by 2030 1,2. In clinical practice and research, the anthropometric method is used to diagnose an adolescent, and the most commonly used indicator is body mass index (BMI) 3,4. A teenager is overweight in the 85th - 95th percentile and obese in the 95th 5. In Chile, 25% of adolescents are overweight and 20% obese. However, in Spain, obesity exceeds 12.6%, and overweight 26.0% 6,7. Anzolina et al. (2016) assessed BMI cut-off points' sensitivity and specificity to predict overweight/obesity according to DEXA estimated body fat values in adolescents. BMI showed a good deal with DEXA, sensitive and specific in identifying overweight and obesity 8.

Obesity alone does not increase cardiovascular risk. Subcutaneous fat has a greater cardiovascular risk for a centripetal android pattern associated with visceral fat. For example, some obese people do not develop insulin resistance or other cardiovascular risk factors related to metabolic syndrome. For this reason, BMI does not always predict cardiovascular risk. Overweight or obese children who become obese adults have an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis 9.

Regular physical activity reduces myocardial oxygen demand and increases cardiorespiratory capacity, with lower coronary risks. Physical activity also reduces systolic and diastolic pressure, improves insulin sensitivity and blood glucose control, reduces glycosylated hemoglobin, and improves dyslipidemia. Physical activity also controls body weight and fat levels. Arango et al. (2020) found an association between high blood pressure, overweight and low cardiorespiratory physical condition 10.

Biological, social, and behavioral changes arise in adolescence, critical to adopting a healthy lifestyle, where exercise levels decrease 11. Lifestyle depends on social and environmental influences, which have transformed adolescents' attitudes, with an intake of low-cost unhealthy foods and reduced exercise 12. In addition, globalized societies evolve into a sedentary lifestyle, fostering a teen's passive attitude, a digital native and full-time computer user, television, remote control, and video games 13. The recommended level is 60 minutes daily of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity, incorporating strengthening three times per week.

Inadequate feeding practices are observed in adolescence 14. Obesity in youth is associated with asthma, sleep disorders, exercise intolerance, hypertension, and negative self-image 15. Obesity in adolescence is an independent risk factor for adult obesity 16. Intervening early, preventing, and controlling obesity is essential to reduce these negative consequences 17. To obesity, it is necessary to improve dietary intake, increase exercise, reduce sedentary lifestyles, and promote healthy lifestyles 18. Therefore, it is relevant to execute strategies in adolescents with lifestyle changes, healthy diet, and daily exercises to improve their nutritional status 19.

Schools are ideal for teenagers because they spend most of their time in school having access to sports facilities for exercise. However, Dobbins et al. in 2013 report that school interventions do not increase physical activity rates in adolescents, nor do they reduce BMI 20. By contrast, Waters et al. in 2011 indicate that exercise effectively reduces body fat 21. On the other hand, Peirson et al. (2015) suggest that behavioral interventions for obesity in young people moderate BMI 22. These authors used different criteria for the type and combination of exercise, intervention time, and age of the participants when obtaining their conclusions.

Several authors have studied the effect of exercise. Kelley et al. (2014) value studies from 4 to 26 weeks in overweight and obese children and adolescents with a change of -0.06 kg/m2 23; Lavelle et al. (2012) study changes in children under 18 years of age with interventions of 2 to 72 months with a change of -0.1 kg/m2 24; Metcalf et al. (2012) study children and adolescents with interventions of 4 to 140 weeks with a change of 0.1 kg/m2 25. However, all these researches were conducted with different criteria to analyze the results and unequal age limits, heterogeneous treatment times, and various intervention types.

Because of the above, the following question arises: What is the effect of physical exercise for 12 weeks on adolescents' nutritional status? It is objective: To determine the impact of training on adolescents' nutritional status in clinical trials for twelve weeks compared to a control group. This systematic review focuses on health promotion actions that develop personal skills or behaviors, effectively reducing adolescent obesity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review respects the PRISMA declaration and Cochrane collaboration. The strategy "PICOS" is used for the research question: Population - Adolescents; Intervention - twelve weeks of exercise; Comparison - Control Group; Outcome - Effect on BMI; and Study design - Clinical trials.

Inclusion criteria: 1) population of adolescent women and men, 2) BMI results, 3) clinical trials, 4) exercise and control studies, 5) Spanish, English, or Portuguese, 6) publications until February 2021.

Exclusion criteria: 1) absence of relevant information from the study, 2) different publications by authors with the same sample, 3) unsuitable design, intervention, or display when reading the full text.

Search for studies: the research team searched six databases: PUBMED, WEB OF SCIENCE, SCOPUS, SCIELO, BEIC, and JSTOR. We used the combination of terms (Mesh): Adolescent; Exercise; Body mass index, Clinical trial.

Selection of studies: the team reviewed the titles and summaries, applying the inclusion criteria and supporting in the case of discrepancies. The grounds for exclusion were documented.

Participants: adolescents, verifying ethical compliance with research.

Intervention: structured physical exercise that increases energy expenditure, practiced systematically (frequency, intensity, and duration), designed to maintain and improve health and supervised by health or education professionals, with aerobic or strength exercises. Yoga, tai chi, or manual therapy were excluded.

Results measures: effect on the BMI mean, with its standard deviation. The formula was used to calculate the Standard Deviation √ [(DE pre 2 + DE post 2) /2].

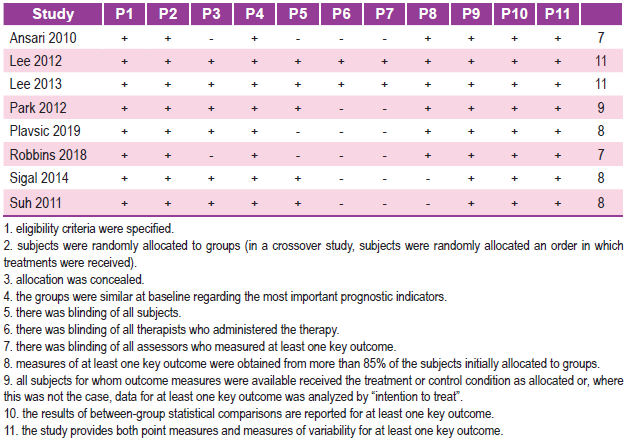

Quality assessment: with the scale "Physiotherapy Evidence Database" consisting of eleven items to evaluate clinical trials' internal validity and statistical information. Studies with scores equal to or greater than five can be considered studies of high methodological quality and low risk of bias.

Data extraction: The full text was revised by extracting the data and performing the synthesis. The main result was the effect on the BMI mean, including its standard deviation. Secondary data were also considered the article's descriptive characteristics (country, year, and sample), the characteristics of interventions, and statistically significant results.

Data analysis: they are presented in tables and figures of the BMI change. For the combined analysis, standardized mean (MD) differences were calculated with the respective confidence interval at 95% accuracy (95% CI) and a significance value of p < 0.05. A random-effects model was used in heterogeneity or a fixed-effects model in the absence of heterogeneity. Mix 2.0 pro software was used for the calculation of effect estimates.

This study has some limitations on using different bibliographic databases and different languages to avoid publication bias.

RESULTS

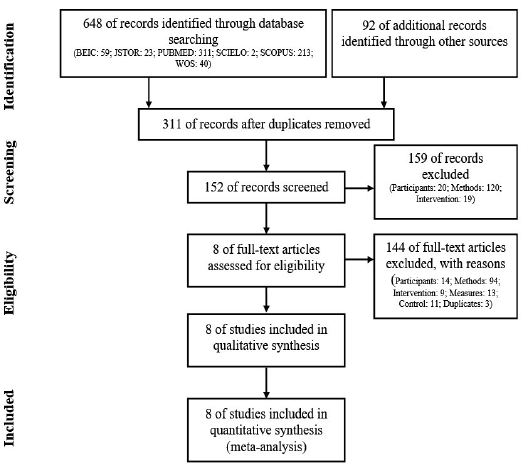

Characteristics of the studies: 740 articles were identified, applying the selection criteria. Of these, eight studies 26-33 were analyzed (n: 761). Figure 1 presents the flowchart and the selection of tasks. Table 1 shows the risk assessment of the studies' bias, offering a low risk of bias and high methodological quality (PEDRO: 8.6 ± 1.5).

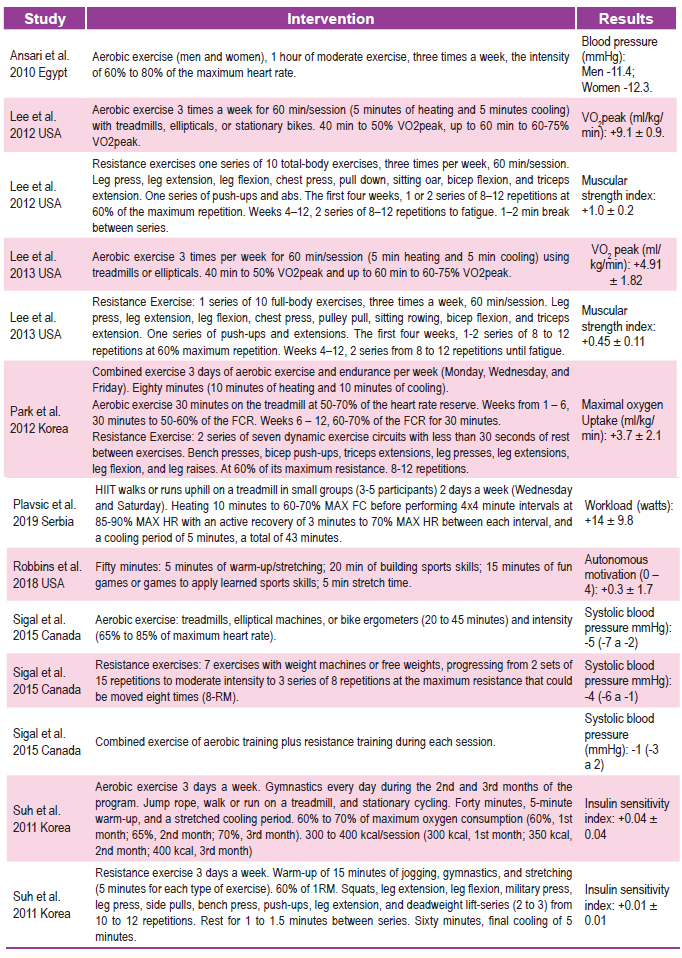

Characteristics of the participants: Table 2 presents the eight studies, which included the following countries: Egypt, the USA, South Korea, Serbia, and Canada, with 761 participants. The initial mean BMI was 29.9 ± 3 kg/m2.

Characteristics of the interventions: the intervention with exercise was for twelve weeks and produced different physiological, functional, and structural improvements in adolescents.

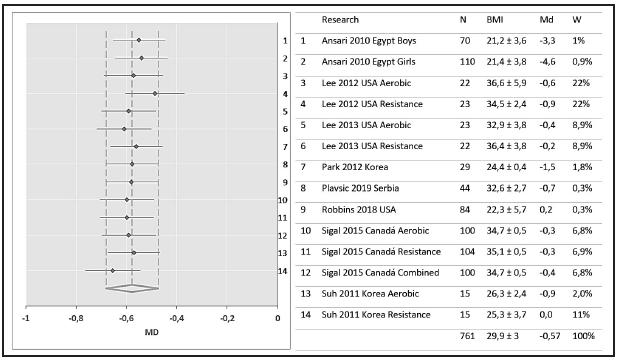

Estimates of the effect of exercise interventions on BMI: Figure 2 shows the eight studies included in the meta-analysis. The random-effects model found that exercise significantly reduced adolescents' BMI by -0.57 Kg/m2 (-0.68 to -0.47) < 0.01. Statistical heterogeneity (I2: 89 %).

The results of each study for this age group are presented in Table 2. Of the eight included studies targeting adolescents, these provided appropriate BMI data for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Of those included in the meta-analysis, a standardized difference in BMI change from the beginning to the end of the intervention between the intervention and control groups was -0.57 Kg/m2 (95% CI -0.68 to -0.47). This result is statistically significant but presents a high heterogeneity in the studies. Thus, the small number of studies and the heterogeneity observed from the plans in the meta-analysis limit our ability to determine the effectiveness of interventions in adolescents confidently. However, these results are promising for promoting physical activity in overweight adolescents, for improving their nutritional status and physical health.

Physical activity outcomes were measured in all studies, and all eight studies report an indicator of the positive impact of physical activity intervention in adolescents (Table 2). Ansari et al. (2010), with an aerobic exercise intervention three times a week with an intensity of 60% to 80% of the maximum heart rate, improved systolic pressure. On the other hand, Lee et al. (2012), with aerobic exercise 3 times a week, improved the VO2 peak. Moreover, resistance exercises with two sets of 8-12 repetitions until fatigue improved the muscle strength index. In another study, Lee et al. (2013), with the anaerobic intervention of 60 min, improved the VO₂ peak and with resistance exercises of 2 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions until fatigue, improved the muscular strength index. Park et al. (2012), with a mixed intervention of 3 days of aerobic exercise and treadmill resistance at 50-70% of the heart rate reserve and resistance of 2 sets at 60% of their maximum resistance with 8-12 repetitions, improved the maximal oxygen uptake. Plavsic et al. (2019), with 4x4 minute intervals at 85-90% of the maximum heart rate, improved the workload (watts). Robbins et al. (2018), with 20 min of building sports skills, 15 minutes of fun games, improved autonomous motivation. Sigal et al. (2015), with aerobic training of 20 to 45 minutes at 65% at 85% of the maximum heart rate and resistance exercises of 3 sets of 8 repetitions at maximum resistance (8-RM), improved systolic blood pressure. Suh et al. (2011), with aerobic exercise 3 days a week, from 60% to 70% of maximum oxygen consumption and resistance three days a week, to 60% of 1RM, with 2 - 3 Series of 10 12 repetitions, improved the Insulin sensitivity index.

DISCUSSION

Several interventions reduce obesity, and it is necessary to know which specific components are most effective, affordable and cost-effective, for use in schools. Amini et al. (2015) indicate that dietary strategies, exercise, or reduced sedentary lifestyles impact fat decline. George et al. (2017) suggest that for adolescent obesity, an increase in physical activity should be emphasized rather than a change in diet due to the possible adverse effects of inappropriate eating patterns that may develop in adolescents 34. Teenagers enjoy activities such as hiking, ice skating, or swimming. Sharma et al. (2006) indicate that schools are essential for implementing exercise programs with adolescents 35. On the other hand, Dobbins et al. (2013) show that adolescents have limited capacity to adopt new behaviors and knowledge.

Although BMI does not measure body composition 36, it has widespread use in epidemiological studies due to its ease of measurement, high data availability, and its relationship to morbidity and mortality 37. Possibly, the outcome of this review seems imperceptible, but it generates changes in body composition that are not identified with BMI and improves health-related quality of life in adolescents.

Unfortunately, BMI does not distinguish between fat mass and lean mass 38. For this, the BMI can be supplemented with the abdominal perimeter, waist-to-hip ratio, or waist-to-height ratio 39. Another option is the measurement of skin folds in adolescents to diagnose and analyze body composition changes during the treatment of childhood obesity 40. Obesity is multifactorial; therefore, exercise interventions can enhance their effectiveness, in the long run, to decrease obesity in adolescents.

A limitation of our research is language due to the lack of an accurate translation that allows us to evaluate and analyze other analyses. Also, this would influence the ability of the team to analyze other databases, to avoid publication bias. Another limitation is the body mass index which does not evaluate changes in body composition but is widely used in research and clinical evaluation of adolescents. We propose using different anthropometric methodologies (4) to assess body composition in adolescents, which are low-cost using field tools, which would allow obtaining better clinical results in the adolescents intervened. In addition, in this review, we also used a qualitative analysis, due to the heterogeneity of the studies, to evaluate the effectiveness of exercise in modifying the nutritional status of adolescents after 12 weeks of intervention.

CONCLUSION

Exercise effectively decreases BMI in adolescents after twelve weeks. Moreover, it can be implemented in schools, fostering positive attitudes towards training, guiding it according to the development level, seeking satisfaction, improving the quality of life-related to health, self-esteem, and extracurricular activities.

While it is necessary to use multiple strategies to decrease obesity, our review indicates that exercise for twelve weeks effectively reduces BMI in adolescents. However, from a clinical point of view, twelve-week exercise interventions may not effectively change adolescents' nutritional status with obesity. Exercise supplemented with healthy dietary habits throughout the school period could have more significant effects.

Acknowledgments

To the Research Directorate of the Universidad Santo Tomás, Universidad Mayor, Universidad de la Frontera and Universidad Pablo de Olavide, for its constant support for research.

STATEMENT

I certify that I have contributed directly to the intellectual content of this manuscript, to the genesis and analysis of its data, for which I am in a position to I am publicly responsible for it and I accept that my name appears on the list of authors. I certify that this work (or important parts of it) is unpublished and will not be sent to other journals. I certify that have met the ethical control requirements.

In the column "Participation codes" I personally write down all the code letters that designate / identify my participation in this work, chosen from the following table:

Conception and design of the work g Contribution of patients or study material

Gathering / obtaining results h Obtaining financing

Analysis and interpretation of data i Statistical advice

Drafting of the manuscript j Technical or administrative advice

Critical revision of the manuscript k Other contributions (define)

Approval of its final version

Conflict of interest: There is no possible conflict of interest in this manuscript. If it'd exist, will be declared in this document and / or explained on the title page, by identifying the sources of financing.