INTRODUCTION

The sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L [LAM]), is a convolvulaceae from America1, whose roots and leaves contain nutraceutical properties highly valued for consumption2, and also for food security3) (4. It presents a wide range of root pigmentation5, with orange pulp varieties having the highest content of beta-carotene and carotenoids6.

It is tolerant to a wide range of edaphic and climatic conditions, making it one of the crops resilient to climate change7) (8) (9) (10. Traditional farmers have a fundamental role in the conservation and generation of diversity in cultivated species11, alongside indigenous peoples12. Understanding the genetic diversity of this important crop is essential, given the continuous rise in food demand and the need to preserve plant genetic resources"13.

The countries with the highest production of this item are Asia, Africa, and the USA14 and to it occupies the fifth place in world production, after wheat, corn, cassava, and potatoes, which are the most used carbohydrate sources15. In Paraguay, it is called “batata” and “jety” (guaraní), and13 other names in America such as “boniato”, “camote”, “batata doce” (portugués) and sweet potato.

The germplasm characterization determines the expression of highly heritable characters ranging from morphological, physiological, or agronomic characteristics, including agrobotanical traits such as plant height, leaf morphology, flower color, seed traits, phenology, and the overwintering capacity of perennial plants16.

Sweet potato is a cross-pollinated and highly heterozygous crop that results in great variability for crop improvement; knowing about genetic diversity helps the breeder to choose desirable parents for use in breeding programs17)(16. Studies of genetic divergence between genotypes in crops are used to analyze the genetic variability in the collection, identify closer or duplicate genetic materials, and generate parameters for the selection of genetically different parents that, when crossed, enable a greater heterotic effect, increasing the chances of obtaining maximum genetic variability and superior genotypes in generations18.

For the analysis of genetic diversity, several multivariate statistical procedures are available, such as grouping analysis or clustering. The diversity study carried out by cluster analysis has the purpose of bringing together, by some criterion of similarity or dissimilarity, the parents of various groups, in such a way that there is greater homogeneity within the group and greater heterogeneity between groups19. Cluster analysis is a useful tool because it can group objects by the degree of similarity sufficient to bring them together in the same set20.

There are other more specific and advanced methodologies for the analysis of genetic diversity21 that can offer more detailed results, but are usually more expensive to execute, such as the use of molecular technology, which is a challenge for some institutions, as it requires advanced laboratory facilities and technical capacity22.

To understand the genetic diversity of sweet potatoes, both morphological and molecular markers have been used 23) (24. Morphological descriptors are potentially useful for clonal identification, due to their high variability and the estimation of genetic distances25, and have been used as a first step to understanding both plant diversity and the conservation of plant genetic resources26.

In genetic improvement programs, which include a selection of superior genotypes, it is necessary to have information about the germplasm to be used, its genetic potential and genetic parameters intrinsic to the characteristics that are to be improved27.

In some Latin American countries, including Paraguay, some factors postpone in-situ and ex-situ conservation and study of this species, mainly resources for research, advancement of extensive agriculture, and migration of farmers and indigenous people. The objective of this work was to characterize the genotypes of a collection and obtain preliminary data on the genetic diversity of sweet potatoes, identifying those most promising for genetic improvement programs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The research was conducted at the Experimental Field of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences (FCA) of the National University of Asunción (UNA), San Lorenzo (25°21ʼS and 57°27ʼW, 125 msnm). The place's average minimum and maximum temperature is 24°C and 32°C, respectively, with an average annual rainfall of 1,400 mm28. The results of the soil analysis indicate that the experimental area belongs to the order Ultisol and sandy loam texture with the following properties: pH= 6.28, organic matter= 0.47%, P= 9.03 (mg/kg), Ca -2= 1.30 cmolc/kg, Mg+2 = 0.54 cmolc/kg, K+= 0.16 cmolc/kg, Al+3 + H+ = 0.

Twenty-six sweet potato genotypes were evaluated, obtained from the sweet potato collection of the UNA/FCA Experimental Field and the Paraguayan Institute of Agrarian Technology (IPTA) collected from producer’s farms.

The genotypes and corresponding numbering are: Moroti (1), Taiwanes (2), Morado (3), Pyta (4), Sa'y jú (5), Moroti Guazú (6), Boli (7), Pyta Uruguayo (8), Pyta Guazú (9), Yety Mandió (10), Taiwanes2 (11), Uruguayo (12), Dacosta (13), Yety Paraguay (14), Andai (15) and hybrid clones obtained by natural polycrossing: Ib-003 (16), Ib-005 (17), Ib-006 (18), Ib-010 (19), Ib-011 (20), Ib-012 (21), Ib-018 (22), Ib-019 (23), Ib-020 (24), Ib-022 (25) and Ib-023 (26) (Table 1, 3).

The experimental design was randomized complete block design, with 26 treatments, where each genotype corresponds to one treatment and three replicates, totaling 90 experimental units (EU). Each UE consisted of four rows of 3.0 m long and 3.0 m wide, separated from each other by 2 m streets, with a useful area of 6.0 m2 and 11 plants per row. Planting was done from branches with 6-8 nodes.

The harvest was carried out 150 days after planting and the following evaluations were made: total productivity, commercial and non-commercial root yield (t ha-1), the total number of roots per plant and biomass of the aerial part (stem, leaves and petioles) (t ha-1). A commercial root was considered as that with mass equal to or greater than 100 g, without damage or deformation29. In addition, the characterization of root shape and color was carried out according to the descriptors of Huaman5.

For the grouping, the UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group with Arithmetic Mean) hierarchical method where the agglomeration criterion is the average distance of all the individuals of a conglomerate with all the individuals of another30.

The Mojena Criterion is a method used to determine the optimal number of clusters or groups in cluster analysis. It is based on the concept of the Quadratic Euclidean Distance31, which measures the dissimilarity between data points within a cluster and measures the quality of the grouping using the Cophenetic correlation coefficient32. This value measures the correlation between the initial and final distances with which individuals have joined during the development of the method. Afterward, an analysis that explored and described each cluster in detail was conducted.

The study of the characters’ relative importance in the genetic divergence prediction was carried out based on the method proposed by Singh33 and the Scott and Knott method34 for comparing the means of the significant variables. For statistical analyses, the software RStudio Team35 was used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

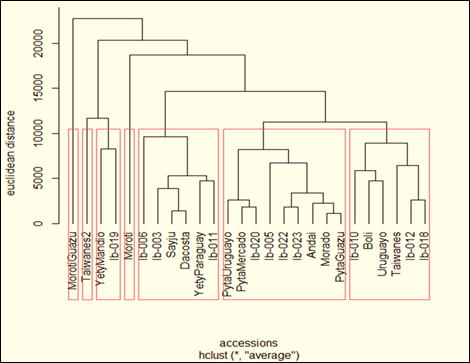

The UPGMA hierarchical method with Euclidean distances managed to group the genetic materials through their five agronomic characters into sevens (Figure 1) using the Mojena criterion31. The cophenetic correlation coefficient gave a value of 0.75, indicating an adequate adjustment in the grouping. Seven groups were defined and distributed according the genetic distance among 26 accessions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Dendrogram of genetic distance of agronomic characters of sweet potato accessions. UNA-FCA, San Lorenzo, Paraguay. 2018

Seven distributed clusters were defined based on the genetic distance between 26 accessions. The largest number of accessions was grouped in Cluster III, with nine accessions, cluster II with six accessions, cluster IV, with six accessions, cluster VII with two accessions, and Clusters I, V, and VII with one accession each (Figure 1, Table 1). The genotypes grouped under the same cluster would have little genetic divergence from each other, which is why greater segregation is expected in crosses between different groups or clusters. The accessions grouped in Cluster III present superior characteristics in the variables studied and the accessions grouped in Cluster IV present characteristics of lower productivity. To obtain genetic variability, those accessions that are found with a greater Euclidean distance from each other should be considered.

On the other hand, accessions that present desirable productive characteristics in a collection can be directly selected by the plant breeder as promising.

The cultivars of a group have the same or almost the same characteristics that simplify the process of selecting crosses from a collection or germplasm bank36.

The knowledge of genetic divergence generates parameters for the selection of parents that, when crossed, enable a greater heterotic effect in their descendants18, increasing the possibilities of obtaining superior genotypes in segregating generations37.

Table 1: Agronomic characteristics of four sweet potato clusters expressed as average. UNA-FCA, San Lorenzo, Paraguay. 2018.

| Cluster | Root productivity (t ha-1) | Comercial root yield (t ha-1) | Not commercial root yield (t ha-1) | Comercial root number | Not comercial root number | Total number of root | Biomass (t ha-1) |

| Cluster I | 24,9 | 1,3 | 3,6 | 2,4 | 1,78 | 4,2 | 15,8 |

| Cluster II | 22,3 | 19,8 | 2,4 | 2,5 | 1,6 | 4,1 | 26,8 |

| Cluster III | 23,1 | 20,6 | 2,5 | 2,6 | 1,6 | 4,2 | 36,4 |

| Cluster IV | 9,1 | 7,3 | 1,8 | 1,57 | 1,6 | 3,2 | 32,8 |

| CLuster V | 10,6 | 9,2 | 1,4 | 1,3 | 0,9 | 2,3 | 50,5 |

| Cluster VI | 39,0 | 35,4 | 3,6 | 3,7 | 2,2 | 5,9 | 25,4 |

| Cluster VII | 37,9 | 34,5 | 3,4 | 2,4 | 2,4 | 4,8 | 36,6 |

Cluster I: Moroti; Cluster II: Taiwanes, Boli, Uruguayo, Ib-010, Ib-012, Ib-018; Cluster III: Morado, Pyta, Pyta Uruguayo, Pyta Guazú, Andai, Ib005, Ib-020, Ib-022, Ib-023. Cluster IV: Sayju, Dacosta, Yety Paraguay, Ib-003, Ib-006, Ib-011; Cluster V: Moroti Guazu; Cluster VI: Yety mandio; Ib-019; Cluster VII: Taiwanes2.

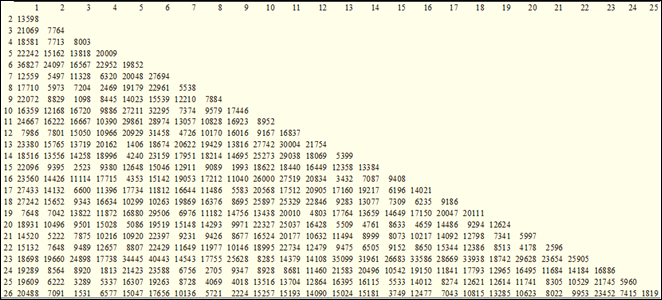

The proximity matrix of Euclidean distances (Figure 2), the proximities of the distances are observed that, when individuals with a greater Euclidean distance from each other are used as parents, greater genetic variability could be obtained.

Figure 2: Matrix of dissimilarity or proximity measures of 26 sweet potato genotypes using Euclidean distances considering five agronomic characters. UNA-FCA San Lorenzo. Paraguay. 2018

The most similar genotypes are Morado3 and Pyta guazú9 with a Euclidean dissimilarity measurement value of 1098, indicating the existence of little genetic variability between similar genotypes or those with lower Euclidean distance. The genotypes Morotí Guazú6 and Ib-01923 presented the greatest distance measurement equivalent to 40,443, indicating that they are the least similar among the 26 genotypes evaluated, therefore, to achieve heterozygous offspring it is necessary to choose parents with the greatest Euclidean distance.

Understanding the genetic diversity in a germplasm collection is of great importance, as it allows the identification of duplications of accessions, which can be eliminated and thus reduce space and operational costs in conservation.

Among the characters studied in the diversity of the genotypes, it is observed that root productivity and total number of roots presented the highest percentage of relative contribution, with values of 48.32% and 14.61%, respectively, which indicates that the Groupings of genotypes were predominantly influenced by these characteristics and they differed on these variables (Table 2).

The interest in the evaluation of a smaller number of variables, which contribute to the discrimination of genotypes, enables savings in time and labor, both in data collection and in the management of the experiments, in addition to reducing costs in future analyses18. In this sense, biomass and commercial yield constitute the least important characteristics for the set of accessions characterized in this work (Table 2). The productivity of the green mass of branches does not influence the root format and the total and commercial productivity of roots, but it can interfere with the size of the roots, and larger branches, they tend to form larger roots38.

Contribution of leaf size for genetic distance found higher39, characters with lower contribution should be discarded for future studies40. It was found a lower contribution for the weight of non-commercial roots and a higher contribution for the total number of roots41 also, it found a more significant contribution for the yield of roots and individual storage of roots, for the genetic distance in sweet potato42.

For root productivity, genotypes 23 (Ib -019) and 11 (Yety Mandió) formed the cluster with the highest yield with values of 41.9 t ha-1 and 37.9 t ha-1, respectively. The high coefficient of variation for this parameter indicates the existence of variability (Table 3). Other authors, it found a total root yield of 43.0 t ha-1, a value higher than that of this research work41 meanwhile, obtained root yields of 12.0 t ha-1 in the best genotype evaluated42; being this result lower than those obtained in this experiment.

Table 2: The relative contribution of characters to the genetic distance of sweet potato clones. UNA/FCA, San Lorenzo, Paraguay. 2018 S. J. Estimated value of Singh's methodology (1981)

| Variables | S.J* | Valor (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Root Productivity | 4268.2 | 48.3 |

| Comercial root yield (t ha-1) | 1098.3 | 12.4 |

| No comercial root yield (t ha-1) | 1235.9 | 14,0 |

| Total root number | 1290.4 | 14.6 |

| Biomass (t ha-1) | 939.7 | 10.6 |

Under local conditions, on a producer's farm, productivity is less than 10 t ha-143, therefore, the values found in the accessions studied can be considered promising for the selection of parents with high productive potential. For productivity, all genotypes greater than 20 t ha-1 are considered to have high potential, and they are the genotypes Yety mandió10, Pyta Uruguayo8, Ib-020 (24), Moroti1, Taiwanes2, Boli7, Uruguayan12, Ib-00517, Ib-02326, Pyta4, Ib-02225, Morado3, Ib-01019 and Pyta Guazu9.44Although the variability of fresh weight is an intrinsic characteristic of the plant material, as well as the variety, climatic conditions, agronomic practices, and growth form of the storage root in a certain type of soil, it affects the acceptability and preference of the consumers.

In the analysis of commercial root yield, genotypes Ib-1923, Taiwanes211, Yety mandió10, Pyta uruguayo8, and Ib -02024 obtained values higher than the other genotypes between 38.6 and 30.7 t ha-1, and genotypes 6.18, and 20 between 12.41 and 10.7 t ha-1 presenting a high coefficient of variation (37.5%) (Table 3) so it is inferred that there is variability between the genotypes for this variable, also considering the environmental factor and cultural management that affect this feature. 45Studies indicate that the amplitude of variation in productivity demonstrates that there is genetic variability, evidencing a situation favorable to improvement, when the objective is the selection of superior genotypes.

In relation to non-commercial root yield, the Taiwanes2 and Moroti1 genotypes present 4.7 and 4.5 t ha-1 of non-commercial roots and and genotype Pyta(4 ) presented the lowest value (Table 3). Other researchers41 found an average yield of commercial and non-commercial roots of 23.0 t ha-1 and 19.0 t ha-1 respectively. On the other hand46, when evaluating sweet potato genotypes, obtained means of 31.2 t ha-1 and 6.2 t ha-1, for the same variables. For the number of roots per plant, the genotypes Ib-02023, Pyta Guazu8, Taiwanes2, and (Morado 3 presented the greatest number of roots, with means of 6.97; 6.37; 6.11, and 5.81 roots plant-1 respectively, which are also among the most productive.

For biomass, 14 genotypes obtained statistically similar values, between 50.53 and 32.39 t ha-1, and eight genotypes obtained statistically similar biomass values between 31.1 and 27.4 (Table 3). In general, genotypes with high biomass values resulted in lower storage root values. 47Biomass is an important indicator in terms of the efficiency of the species in the use of the environmental and genetic resources available to it. Likewise, it provides an idea of its potential, depending on the amount of fresh material it can provide for different uses.

Tabla 3: Agronomics characteristics of 26 sweet potato genotypes. UNA-FCA, San Lorenzo, Paraguay.

| Root productivity (t ha-1) | Comercial root yield (t ha-1) | No comercial root yield (t ha-1) | Total number of root per plant | Biomass (t ha-1) |

| Genotype | Genotype | Genotype | Genotype | Genotype |

| 23 41,8 a | 23 38,6 a | 2 4,7 a | 23 6,9 a | 6 50,5 a |

| 11 37,9 a | 11 34,5 a | 1 4,5 a | 8 6,4 a | 17 43,0 a |

| 10 36,2 b | 10 32,2 a | 10 4,0 a | 2 6,1 a | 18 40,3 a |

| 8 33,5 b | 8 30,8 a | 25 3,8 a | 3 5,8 a | 9 37,6 a |

| 24 32,9 b | 24 30,8 a | 26 3,6 a | 25 5,3 b | 15 37,2 a |

| 1 29,4 c | 1 26,9 b | 11 3,4 a | 10 4,8 b | 11 36,6 a |

| 2 29,4 c | 2 25,3 b | 5 3,3 a | 11 4,7 b | 3 36,6 a |

| 7 27,6 c | 7 24,9 b | 3 3,3 a | 19 4,3 c | 26 36,2 a |

| 12 27,5 c | 4 24,9 b | 23 3,2 a | 5 4,3 c | 25 35,4 a |

| 17 26,8 c | 12 24,5 b | 12 3,0 a | 1 4,2 c | 16 34,5 a |

| 26 26,3 c | 19 22,7 b | 8 3,0 a | 24 3,9 c | 24 34,3 a |

| 4 25,6 c | 26 22,6 b | 9 2,8 a | 14 3,9 c | 4 33,8 a |

| 25 24,7 c | 3 21,7 b | 7 2,6 a | 21 3,6 c | 8 33,2 a |

| 3 24,6 c | 25 20,9 b | 13 2,3 b | 12 3,7 c | 13 32,4 a |

| 19 24,5 c | 17 18,3 c | 24 2,3 b | 7 3,7 c | 5 31,1 b |

| 9 20,5 d | 9 17,6 c | 17 1,9 b | 26 3,5 c | 20 31,0 b |

| 15 17,7 d | 15 16,2 c | 20 1,9 b | 17 3,4 c | 2 29,3 b |

| 21 17,6 d | 22 16,1 c | 14 1,8 b | 9 3,1 c | 21 29,1 b |

| 22 17,5 d | 21 15,9 c | 21 1,7 b | 13 3,1 c | 22 28,5 b |

| 6 14,1 e | 6 12,4 d | 6 1,7 b | 20 3,0 c | 10 27,9 b |

| 18 12,4 e | 18 11,5 d | 19 1,5 b | 15 3,0 c | 7 27,8 b |

| 20 12,1 e | 20 10,2 d | 15 1,5 b | 22 2,9 c | 14 27,5 b |

| 5 10,6 e | 16 93,6 d | 22 1,4 b | 4 2,8 c | 12 23,1 b |

| 16 10,3 e | 5 72,6 d | 18 1,1 b | 16 2,5 c | 19 23,0 b |

| 14 87,9 e | 14 70,2 d | 16 1,0 b | 18 2,4 c | 23 22,8 b |

| 13 85,8 e | 13 +62,9 d | 4 0,7 b | 6 2,3 c | 1 15,8 b |

| C.V (%) 28,6 | 32,3 | 37,5 | 28 | 23,1 |

Gen: Genotype. Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ from each other according to the Test of Scott-Knott test (p= 0.05), C. V: Coefficient of variation. Moroti (1), Taiwanes (2), Morado (3), Pyta (4), Sa’y jú (5), Moroti Guazú (6), Boli (7), Pyta Uruguayo (8), Pyta Guazú (9), Yety Mandió (10), Taiwanes2 (11), Uruguayo (12), Dacosta (13), Yety Paraguay (14), Andai (15) Ib-003 (16), Ib-005 (17), Ib -006 (18), Ib -010 (19), Ib -011 (20), Ib -012 (21), Ib -018 (22), Ib -019 (23), Ib -020 (24), Ib -022 (25) y Ib -023 (26).

In relation to the qualitative descriptors for root (Table 4), the elliptical shape is found in a higher percentage (46.2%) and the obovate shape in a lower percentage (3.8%). The local consumer generally prefers elongated shapes, and roots of medium thickness, which stand out for culinary use in preparations preferably boiled. However, in gastronomy, there is a wide variety of preparations such as baked and fried. The characteristic, more elongated roots of elliptical shapes, rather than round or oblong, is another objective proposed for the selection of varieties. Those varieties44 of various shapes can be used for agroindustry.

Table 4: Participation of 26 sweet potato genotypes for qualitative root nominal scale descriptors. UNA-FCA, San Lorenzo, Paraguay. 2018

| Descriptor | Porcentaje (%) | |

| Root shape | Round | 15,4 |

| Long eliptic | 34,8 | |

| Obovate | 3,8 | |

| Elíptic | 46,2 | |

| Skin Color | Crem | 53,8 |

| Yellow | 7,7 | |

| Predominant colour | Dark purple | 19,23 |

| Red-purple | 15,38 | |

| Orange | 3,8 | |

| Predominant colour intensity | Pale | 15,4 |

| Intermediate | 38,4 | |

| Dark | 46,1 | |

| Flesh Colour | Cream | 23,7 |

| Predominante colour | Dark ream | 11,5 |

| Pale yellow | 46,1 | |

| Secundary flesh colour | Ausent | 50 |

| White | 7,6 | |

| Cream | 3,8 | |

| Orange | 19,2 | |

| Yellow | 15,3 | |

| Red purple | 3,8 | |

| Dark purple | 3,8 |

The sweet potatoes collection consists mainly of cream-colored skin (53.8%) with dark purple (19.2%) and purplish red (15.4%) also present in significant amounts. Yellow (7.7%) and orange (3.8%) are present in smaller percentages. The predominant color has a higher percentage of dark shades (46.1%). The meat color is mainly pale yellow (46.1%), and the secondary color is absent in 50% of the samples, with other colors present in smaller percentages. These different shapes and colors highlight the variability in these descriptors (Table 4).

In marketing establishments, the purple-skinned sweet potato is prevalent, suggesting that it is the preferred pigment for local consumers. This characteristic should be taken into consideration for future improvement programs. The purple pigment has a higher content of beta-carotene and carotenoids6.

CONCLUSION

The UNA/FCA collection presents sweet potato genotypes that can be used for genetic improvement programs. The genetic distances of the studied germplasm are grouped into seven clusters. Some characters, such as biomass, had less importance for diversity, with total root productivity being the variable that contributed the most to genetic distance.

There is variation in the studied population that can be used for genetic improvement related to productivity per hectare and per plant, root shape and color, since there is the possibility of generating variability between the studied clusters.

uBio

uBio