INTRODUCTION

Children with acute chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection are prone to experiencing severe symptoms due to its rapid transmission. While the majority of infected individuals develop symptoms, usually within 3-7 days of being bitten by an infected mosquito, children may be particularly vulnerable to the virus1. The most common symptoms of this infection include fever and joint pain; however, children may also experience headaches, muscle pain, joint swelling, or rash2,3. In addition, arthralgia and arthritis are reported to be the most debilitating symptoms, affecting 87% of adults and 30-50% of children during the acute stage of infection. Of these patients, 23-36% of pediatric patients and 53% of adults experience post-acute arthralgia4.

Individuals from all age groups are at risk of contracting the virus, but children tend to experience joint manifestations less frequently. In contrast, women appear to have a higher probability of developing debilitating symptoms5. However, severe neuroinvasive diseases related to infection can still occur in children. Additionally, people with existing comorbidities may experience atypical symptoms or even die because of the infection6,7,8,9,10.

In children, CHIKV disease can present with additional symptoms, such as respiratory difficulties, changes in skin color, and generalized weakness, which may necessitate immediate medical attention11. At present, there are no specific medications for treating CHIKV, making prevention and mosquito control crucial for preventing the spread of the disease12. However, in November 2023, the first vaccine against CHIKV, called VLA1553 and commercially known as Ixchiq®, was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adult use only13.

The situation is further complicated by the similarities between CHIKV's symptoms and those of other mosquito-borne diseases, such as dengue and Zika, which can lead to misdiagnoses and delay appropriate treatment5. Moreover, joint pain can be severe and debilitating, persisting for months, and can significantly impact a child's quality of life4,8. Although fatalities from CHIKV are rare, the disease can be more severe in children with concomitant health problems, neonates, or infants14,15,16.

Given these factors, this study aimed to describe the characteristics of acute CHIKV virus infection in children from the Department of Caaguazú, Paraguay, in 2023.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A study on children from Caaguazú was conducted in 2023. This was a retrospective observational study17, and the inclusion criteria were children who had developed symptoms of acute CHIKV infection within the past five days and had a fever of at least 38.5 °C. Children who had a positive antigen or serological test for dengue or zika were excluded.

Confirmed cases were defined as those with positive results by real-time RT-PCR analysis for CHIKV. In view of the possibility of coinfections, real-time RT-PCR was performed, which excluded possible coinfection with dengue or Zika viruses. We collected data on clinical characteristics using a standardized case record form and created an electronic dataset for analysis. The data were analyzed using Stata 14.0® Statistical Software. Pearson’s chi-squared test was performed to determine the association between categorical variables with a 95% confidence level.

This study adhered to the principles of bioethics and obtained approval from the National University of Caaguazú Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

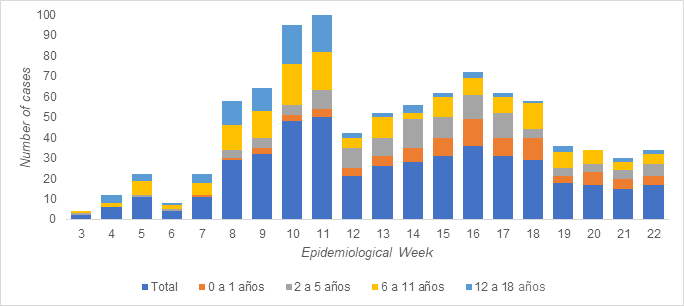

A total of 461 children were enrolled in the study, 51.62% were women. The age groups included infants (0-23 months, n=88, 19.1%), preschoolers (2-5 years, n=115, 24.9%), schoolchildren (6-11 years, n=163, 35.4%), and adolescents (12-17 years and 11 months, n=95, 20.6%). School-aged children constituted the largest proportion of the cases (Figure 1). The female-to-male ratio was 1:1.067.

According to clinical characteristics, fever, headache, rash, myalgia, and arthralgia were more frequently reported. However, we observed variations in these manifestations based on age group. Specifically, school-aged children and adolescents experienced a higher incidence of myalgia (64.6% [p<0.001]) and arthralgia (63.7% [p<0.001]). In contrast, preschoolers, school-aged children, and adolescents were more likely to experience vomiting (89% [p<0.001]), headache (89.4% [p<0.001]), and retro-orbital pain (95% [p<0.001]). Additionally, while rash (39.5% [p<0.001]) and petechiae (18.5% [p<0.001]) were more common in infants, these symptoms were less frequently reported in other age groups (Table 1).

Four children died during the outbreak, including a neonate, two children aged two and three years, and an 8-year-old girl. None of the children had any underlying health condition (Table 2).

Table 1 Distribution of characteristics of children with CHIKV according to age group in Paraguay (n=461

| Characteristics | Infants 0-23 months n (%) | Preschoolers 2-5 years n (%) | Shoolchildren 6-11 years n (%) | Adolescents 12-17 years n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 37 (42.05) | 57 (49.57) | 82 (50.31) | 47 (49.47) | 0.623 |

| Female | 51 (57.95) | 58 (50.43) | 81 (49.69) | 48 (50.53) | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Fever | 66 (98.51) | 85 (97.70) | 132(98.51) | 76 (98.68) | 0.944 |

| Nausea | 21 (25.93) | 34 (33.33) | 53 (34.64) | 42 (47.73) | 0.028 |

| Vomiting | 25 (30.86) | 54 (52.94) | 89 (58.17) | 61 (69.32) | 0.001 |

| Rash | 32 (39.51) | 39 (38.24) | 35 (22.88) | 15 (17.05) | 0.001 |

| Headache | 23 (28.40) | 45 (44.12) | 81 (52.94) | 67 (76.14) | 0.001 |

| Retroorbital pain | 5 (6.17) | 25 (24.51) | 35 (22.88) | 37 (42.05) | 0.001 |

| Myalgia | 32 (39.51) | 49 (48.04) | 84 (54.90) | 64 (72.73) | 0.001 |

| Arthralgia | 37 (45.68) | 58 (56.86) | 98 (64.05) | 69 (78.41) | 0.001 |

| Petechiae | 15 (18.52) | 10 (9.80) | 21 (13.73) | 10 (11.36) | 0.001 |

| Leukopenia | 1 (1.23) | 3 (2.94) | 1 (0.65) | 1 (1.14) | NA |

| Severe abdominal pain | 1 (1.23) | 3 (2.94) | 1 (0.65) | 1 (1.14) | NA |

| Abdominal tenderness | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.14) | NA |

| Persistent vomiting | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.31) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Mucosal bleeding | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.65) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Irritability/drowsiness | 2 (2.47) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Arthritis | 8 (9.88) | 21 (20.59) | 31 (20.26 | 25 (28.41) | 0.028 |

| Skin eruption | 39 (48.15) | 38 (37.25) | 44 (28.76) | 16 (18.18) | 0.001 |

| Conjunctival hyperemia | 1 (1.23) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Pruritus | 3 (3.70) | 8 (7.84) | 6 (3.92) | 3 (3.41) | 0.468 |

| Joint swelling | 8 (9.88) | 5 (4.90) | 7 (4.58) | 6 (6.82) | 0.412 |

NA: not applicable

DISCUSSION

The symptoms of CHIKV infection in pediatric patients reported in our study are consistent with the common symptoms described in the literature. Fever, headache, rash, myalgia, and arthralgia are frequently observed in children with CHIKV infection, as reported in studies9,10,12,18,19,20. It is estimated that 70-93% of patients with CHIKV infection exhibit symptoms, with 3-25% of seropositive patients being asymptomatic and 2-7% experiencing atypical symptoms18. During the acute phase of human infection, CHIKV infection is characterized by a sudden onset of high fever, often accompanied by severe joint pain, headache, and rash20.

We found that school-age stage accounts for a disproportionately large number of cases. The school-age stage has been identified as a demographic group of great significance in contributing to a higher incidence of CHIKV cases, as reported in several studies21,22,23,24. These studies have demonstrated a negative correlation between age and the incidence of CHIKV infection, suggesting that the school-age population may be particularly vulnerable to CHIKV.

The importance of further exploring the disease in diverse age groups, particularly infants, has been highlighted by research findings. Robin et al.25 documented a retrospective hospital-based pediatric series revealing neurological manifestations of CHIKV in children, including encephalitis, febrile seizures, meningeal syndrome, and acute encephalopathy25. Janakiraman et al. discussed CHIKV in infants, challenging the previously held belief that cutaneous manifestations were benign26. Furthermore, Raju et al. 27 described varied clinical presentations and manifestations of CHIKV among different age groups in a case series27. These studies collectively contribute to the comprehension of the diverse clinical aspects of CHIKV infection in pediatric populations.

We found a higher prevalence of myalgias and arthralgias in school-age children and adolescents, a finding consistent with certain studies6,21. However, vomiting, headaches, and retro-orbital pain were less common in infants, although this data may be biased in underestimating pain in infants, as is often the case in clinical practice28. Skin lesions were more prevalent in infants, as reported in the literature10,29. Our results do not show re-hospitalizations, but four fatalities (0.87%) occurred without any underlying pathologies, indicating the potential for severe complications due to CHIKV15,16.

The study's limitations include its retrospective design and incomplete clinical records. Nonetheless, its strength lies in the insights it provides on the clinical presentation of CHIKV in various age groups.

In conclusion, the CHIKV virus outbreak in the Department of Caaguazú, Paraguay, displayed distinct clinical manifestations in children based on age, with fatal outcomes occurring in a small percentage of cases. Therefore, it is crucial to consider preventative measures such as vector control.