INTRODUCTION

The Old World cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armígera is one of the most important agricultural pests in the world. Distributed in Asia, Africa, Europe, Australia and reported in 180 cultivated agricultural crops (Tay 2013). Recently it invaded South and Central America, and it appears to be spreading rapidly (Kriticos et al. 2015). Its voracity is worrisome, in its larval stage can feed on leaves, stems, shoots, inflorescences, fruits and pods (Acevedo Reyes 2015).

In the American continent, its occurrence was reported in several Brazilian regions, which resulted in significant economic losses in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), maize (Zea mays L.) and other crops. In Brazil, the species shows a high adaptation capability, strong population growth, widespread distribution within different regions, and the ability to feed and develop on different host species. Considered a quarantine pest until mid-2013, its presence was officially confirmed by morphological characteristics of the genitalia and by molecular PCR technique in soybean crops in Bahia and cotton in Mato Grosso State (Czepak et al. 2013; Embrapa 2013; Specht et al. 2013; Leite et al. 2014; Sosa-Gómez et al. 2016).

In Argentina, this pest was detected at many locations, confirming the presence of H. armigera for the first time in the Tucuman province (Murúa et al. 2014). Previously, Chiarelli de Gahan & Touron (1954) reported the occurrence of H. armigera in Argentina but clearly this was a misidentification as stated by Hardwick (1965). In 2015, H. armigera larvae was collected from chickpea in Rapelli (Santiago del Estero province), and adults were captured with light traps near leguminous and cotton fields in Las Breñas (Chaco province) North of the country. Also, the propagation of H. armigera to the south to the Argentine belt of corn and soybeans was demonstrated. In fact, adults were caught by light traps adjacent to maize and soybean fields in Marcos Juárez (Córdoba province), at the core of the country’s main agricultural lands (Arneodo et al. 2015).

Specimens of H. armigera from Uruguay were recently identified by molecular characterization at the following locations: Flores, Lavalleja, Cerro Largo and Rocha Departament (Castiglioni et al. 2016). In Paraguay, the National Plant and Seed Quality and Health Service, SENAVE, in 2013, reported its presence in Cantina kué, Alto Paraná Department in soybean crops. However, DNA analysis to confirm the species has not been performed and its distribution in the country is unknown. Thus, the objective of this research was to demonstrate the occurrence of H. armigera, identified by molecular analysis, in the Amambay Department, Paraguay.

To obtain the H. armigera specimens, delta traps were installed with sex pheromone (Iscalure armigera) attached to fixed bases according to the manufacturer's instructions. The traps were distributed in soybean crops located in the municipalities of Pedro Juan Caballero, Zanja Pytã, Capitán Bado, Karapã'i and Bella Vista. In addition, sampling cloth was used for collecting caterpillars. All the specimens collected were pre-selected using description techniques and morphological characteristics for caterpillars and adults corresponding to the genus Helicoverpa (Azambuja 2016). Once individualized in jars containing pure alcohol, they were sent to the Laboratory of Molecular Ecology of Arthropods of the Department of Entomology of the Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz”, ESALQ/USP - Piracicaba/SP/Brazil, where DNA extraction, amplification and identification by PCR-RFLP were carried out.

For molecular identification, DNA extraction of the thoracic tissues of both caterpillars and adults were carried out following the Doyle and Doyle protocol (1990). Head, abdomen, wings, and legs of insects were separated using a scalpel. The thorax was individualized in 1.5 ml microtubes under extractor hood and were added 650 μL of extraction buffer (10 ml CTAB 2% + 20 μg of proteinase K 20 μg / ml + 20 μl β-mercaptoethanol) and crushed with previously autoclaved pistils. Once crushed, the samples were subjected to a water bath at 65ºC for one hour.

Subsequently, 650 μl of CIA 24: 1 (24 chloroform and 1 isoamyl alcohol) were removed and the sample stirred and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 minutes. The supernatant fluid was then extracted with a micropipette and transferred to another 1.5 ml microtube. Again, 650 μl of the CTAB 2% extraction buffer (without proteinase K and β-mercaptoethanol) and 200 μl of CIA 24: 1 were added, being centrifuged as described above. This cleaning process was repeated until the sample was in condition. Once this process was completed, the supernatant fluid was separated into another 1.5 ml microtube by adding 200 μl of isopropanol and kept in a freezer at -20°C for two hours. It was then centrifuged at 12000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes, then the isopropanol was discarded and the resulting pellet was washed twice with 70% alcohol for 10 minutes. Afterwards, the alcohol was discarded and the pellet was left to dry in the overnight vacuum, finally, 49 μl of purified double-distilled water and 1 μl of RNAse were added, and kept in a freezer at -20ºC, to be observed in agarose gel electrophoresis and in this way, evaluated the quality and quantity of extracted DNA, used for amplification in PCR and identification of H. armigera.

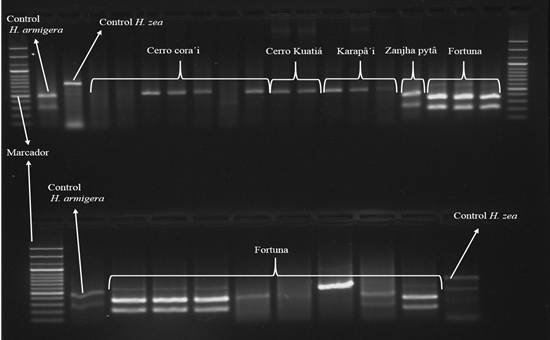

A total of 24 Helicoverpa specimens were analyzed using the PCR-RFLP marker of a fragment of the mitochondrial gene Cytochrome Oxidase Subunit I (COI), previously used by (Specht et al. 2013, Leite et al. 2014). The extracted DNA was amplified by PCR in final volume of 10 μl of reaction containing 1 μl of buffer Taq DNA polymerase (10X), 1.5 μl 25 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of 10 mM dNTP, 1 μl forward primer LCO (F) (59 - GGT CAA CAAATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G - 39), and 1 μl of reverse primer HCO (R) (59 - TAA ACTTCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA - 39), 0.10 μl of taq DNA polymerase, 3.4 μl of purified H2O and 1 μl of diluted DNA (2 μl of DNA extracted in 48 μl of purified water). For the PCR reaction a cycle was performed at 94°C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 40 seconds, 55°C for 40 seconds, 72°C for 70 seconds and a final extension cycle at 72°C for 10 minutes. Next, digestion with the restriction enzyme was performed in another microtube of 5 μl of the PCR product, 2 μl of enzyme buffer, 0.5 μl of restriction enzyme and finally completed with 7.8 μl of purified water giving a final volume of 15 μl and incubated at 37°C for 6 hours or overnight. Finally, the samples were analyzed in 1.5% agarose gel with SYBER SAFE (TAE 1X) and observed in UV ultraviolet transilluminator (Figure 1).

Figure 1 PCR-RFLP Agarose gel (1,5%) for amplification that characterizes the bands of the specimens after cutting with the restriction enzyme (One band: Helicoverpa zea; Two bands: Helicoverpa armigera).

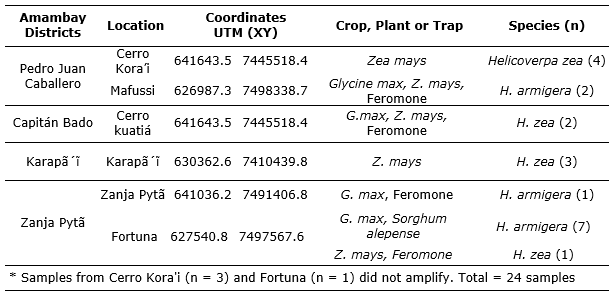

Of twenty-four samples subjected to analysis and characterization by molecular techniques, ten individuals were identified as H. armigera, Zanja Pytã district (a location of Zanja Pytã (n = 1), Fortuna (n = 7) and Pedro Juan Caballero (Mafussi location n = 2). Other ten individuals were identified as H. zea, four specimens from Pedro Juan Caballero district, Cerro Kora'i, three from Karapa’ĩ district, and two from Zanja Pytã district, Cerro Kuatiá location (Table 1, Figure 2). However, four samples did not amplify (Table 1). These results reveal the occurrence of H. armigera in soybean and maize crop 2016/2017 in the Amambay Department, Paraguay.

Table 1 Detection of Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa zea in soybean and maize crops at Amambay districts, identified by molecular analysis.

It is important to consider that H. armigera samples were collected from locations that limit geographically with Mato Grosso do Sul state, Brazil (1 to 20 km) (Figure 2). Extensive areas of soybeans and corn from of Pedro Juan Caballero, Zanja Pytã and Capitan Bado districts form a green bridge between Paraguay and Brazil, which facilitates the dispersal of H. armígera from Brazil to Paraguayan crops, assuming that the pest was detected for the first time in the America continent in Brazil (Czepak et al. 2013).

Figure 2 Detection of H. armigera and H zea in soybean and maize crop 2016/2017 from districts of Amambay Departament, Paraguay.

In Paraguay, the National Seeds and Plants Health Service (SENAVE), reported in 2013 the presence of Helicoverpa sp. in soybean in Cantina kué, a location in the Alto Paraná department, however, only external morphological characteristics were used as mean of identification without carrying out molecular DNA analysis to confirm the species presence

In Brazil, morphological identification was based on the male genitalia and molecular analysis of mitochondrial genes sequences of cytochrome B and the cox1-tRNALeu-cox2 region were amplified, later they were deposited at the GenBank (Embrapa 2013, Czepak et al. 2013, Avila et al. 2013). These H. armigera specimes were captured with light traps. H. armigera has spread to the northeast and the midwestern region of Brazil, causing great losses. Recently, its presence in the state of Minas Gerais, Viçosa, was confirmed by molecular analysis. The insects were collected from transgenic and non-transgenic soybean, cotton and corn crops (Pinto et al. 2017).

The Argentine National Pest Surveillance and Monitoring System (SINAVIMO) also recorded H. armigera in eight provinces and twenty counties in Argentina, in soybean, chickpea, sunflower and cardus Carduus acanthoides crops. Being this the first report of H. armigera in sunflower and cardus in Argentina (Murúa et al. 2014). In the same year, specimens of H. armigera were also identified by molecular characterization in Uruguay at the following locations Flores, Lavalleja, Cerro Largo and the Rocha department (Castiglioni et al. 2016). There is evidence that H. armigera has spread to Uruguay and Paraguay, polymerase chain reaction and sequencing of the partial mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) cytochrome oxidase also supports these findings. Molecular characterization of this gene region from individuals from Paraguay also supports previous morphological identification of H. armigera in Paraguay (Arnemann et al. 2016).

Research about the potential invasion of H. armigera in North America shows that this is a matter of time, given that the species has already been detected in Argentina, Bolivia, Uruguay, Puerto Rico and now Paraguay. Furthemore, the extensive production of host crops, facilitates their abundance and propensity to disperse in wind systems, thus, they will continue to spread beyond South and Central America (Kriticos et al. 2015).