INTRODUCCIÓN

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) is among the most harmful mental health conditions1. Despite this, only around a tenth of people with AUD seek treatment2. Not only is treatment-seeking uncommon, but when it occurs, it is often after decades of recurrent negative consequences3 and many unsuccessful recovery attempts4.

Current efforts to better understand AUDs have led to revisions of the most widely used classification systems5, the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and the ICD (International Classification of Diseases). The DSM-56 is the latest version of a classification system developed specifically for mental disorders. It characterizes AUD as a unidimensional disorder with three levels of severity (mild, moderate, or severe): two to three criteria indicate a mild level, four to five criteria indicate a moderate level and more than five criteria indicate a severe level of the disorder. On the other hand, the latest version of the ICD, the 11th7, distinguishes between alcohol dependence (with similarities to AUD as conceptualized by DSM-5), harmful patterns of alcohol use, and hazardous alcohol use (Saunders et al., 2019). These last two conditions refer to people with some alcohol-related problems in the present and at risk of alcohol dependence in the future. In ICD-11, the number of criteria is not important. Instead, criteria are combined into three guidelines: impaired control, increasing priority, and physiological features. The presence of two of these guidelines indicates alcohol dependence.

There is a lack of information regarding how those two classification systems, DSM-5 and ICD-11, relate to functional features associated with AUD8. Therefore, this study examined how the DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria and classification systems relate to two functional characteristics (functional impairment and subjective distress) as evidence of their concurrent validity. Functional characteristics can provide evidence of concurrent validity because diagnostic systems should be able to detect the level at which a disorder affects different life domains.

Several studies have found associations between AUD, functional impairment and subjective distress9,10. Functional impairment (FI) can be characterized as a person's difficulty in performing adequately in various life domains due to a health condition11, and subjective distress (SD) is the level of non-specific psychological discomfort perceived by the individual12. Recently, Mannes et al8 examined the association between external diagnostic validators, such as impairment or psychiatric disorder, and DSM-5 scores to determine whether this classification system accurately captures the degree to which different life domains are affected. They found that AUD severity (in terms of DSM-5 levels) was related to FI and other diagnostic validators.

Although there is research on FI and SD, studies have mainly focused on them separately. Furthermore, the few studies that have addressed alcohol consumption, FI, and SD together13,14 do not include low-income or Latin American patients and are not specific to people with AUD. The proper study of mental health disorders requires specific information from diverse cultures, and this information gap contributes to the inequality among different regions and countries. Also, this research topic is timely since alcohol-related problems are higher in low-income or lower-middle-income countries1.

Considering some AUD criteria may affect an individual's life more than others15, this paper examines the relationship between each criterion, the ICD-11 and DSM-5 classification systems, and levels of two functional characteristics (FI and SD) in Argentinean hospitalized patients with an AUD. By examining FI and SD, we aim to provide evidence of the concurrent validity of the ICD-11 and DSM-5 classification systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design, setting and participants

This was a correlational cross-sectional study. We interviewed thirty-four (34) treatment-seeking patients that presented voluntarily at the Alcohol Treatment Unit of the Regional Hospital Oscar E. Alende in Mar del Plata, Argentina. This medical unit depends upon the city's only public general hospital and receives mostly low-income patients without private health insurance. Data were collected from a purposive clinical sample. Twenty-nine participants were men (85%), and five were women, with a mean age of 54 years (DS= 9.63), ranging from 34 to 74 years. Years of formal education were between 0 to 20 (M= 7.82, DS= 4.63). Regarding marital status, 35.3 % of the participants were divorced, 29.4 % were currently in a relationship, and 21 % were single. Finally, 41 % of the participants were unemployed, 21% were retired, and 38% had some form of employment, including both salaried and precarious work (i.e., unstable) employment.

Procedure

Patients came voluntarily at the alcohol treatment unit to see a physician. After the medical interview, patients were invited to participate in the study. Only patients who were able to give informed consent (e.g., not highly intoxicated or with severe health conditions) were invited to participate in the study. Participants gave informed consent after verbal and written information about the project was given to them. The data provided by the patients were anonymous and confidential. Thirty-four (34) interviews were conducted by a trained researcher (TS) in an office of the Alcohol Unit between May and October 2018. The interviews had an average duration of 30 minutes, and a structured questionnaire was used.

Alcohol section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)

This questionnaire has been validated in several contexts(16), the alcohol section is compatible with the DSM-5 AUD criteria and the ICD-11 alcohol dependence guidelines(2). This instrument includes questions about the presence of the following criteria during the past year: 1) role impairment, 2) hazardous use, 3) interpersonal problems, 4) tolerance, 5) withdrawal, 6) larger or longer use than intended, 7) repeated attempts or strong desire to reduce or stop use, 8) much time spent using, 9) reducing activities in order to use, 10) physical or psychological problems due to use, 11) and craving. Criteria were recoded based on the ICD-11 classification system (5) for data analyses. Criteria 6, 7, and 11 composed the first ICD-11 guideline: impaired control. Criteria 1, 3, 8, 9, and 10 composed the second ICD-11 guideline: increasing priority. Criteria 4 and 5 composed the third ICD-11 guideline: physiological features. Criterion 2 was not included since it is not considered an indicator of alcohol dependence in ICD-11. As expected in this clinical sample, no participants presented a Harmful Pattern of Alcohol Use or Hazardous Alcohol Use. DSM-5 AUD was coded into mild, moderate, and severe based on the number of endorsed criteria.

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0)

This 12-item schedule to measure FI indicates the degree to which six life domains have been affected in the last 30 days. These six life domains are cognition, mobility, self-care, relationships, daily activities, and community participation11. This schedule has been validated across contexts and health conditions17,18. The WHODAS had high internal consistency in this study, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .87.

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10)

This 10-item scale to measure SD assesses the degree to which the participant has perceived unspecific psychological distress (i.e., felt depressed, anxious, or restless) in the last 30 days. It has been validated in several contexts19,20. A version adapted to the Argentinean population12) was used. In this study, the K10 scale had high internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 92.

Data analyses

A descriptive (frequency) analyses of all variables was performed. It was also used logistic regressions with each criterion as the outcome (0=No/1=Yes) and FI and SD separately as predictors to assess the relationship among AUD criteria, FI, and SD. The same was performed for the three ICD-11 criteria guidelines (0=No/1=Yes). In addition, Spearman correlation coefficients were estimated for the association between the DSM-5 sum of criteria, FI, and SD since all of these variables were non-parametric.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethical Committee from the Regional Hospital Oscar E. Alende, Mar del Plata, Argentina. All procedures followed the national and international ethical standards and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, revised in 2000. Participants received no payment.

RESULTS

Diagnostic Criteria and Functional Characteristics

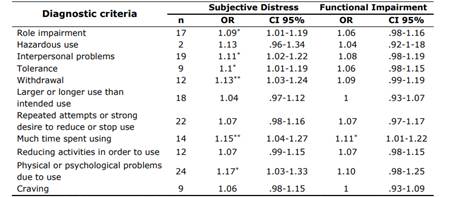

Functional impairment (FI) was weakly related to how much time was spent using the criterion. Very weak associations were found among Subjective Distress (SD) and role impairment, interpersonal problems, tolerance, and physical or psychological problems due to use, and weak among SD and withdrawal and much time spent using (Table 1).

Tabla 1. Diagnostic criteria, Subjective Distress and Functional impairment in 34 help-seeking patients from Mar del Plata, Argentina

Note. CI= Confidence Intervals. SD= Subjective Distress. FI= Functional Impairment. Data was derived from the CIDI interview. Criteria 6, 7, and 11 composed the first ICD-11 guideline: impaired control. Criteria 1, 3, 8, 9, and 10 composed the second ICD-11 guideline: increasing priority. Criteria 4 and 5 composed the third ICD-11 guideline: physiological features. Criterion 2 is not considered an indicator of Alcohol Dependence on ICD-11. *p<.01

DISCUSSION

Mental disorders are a challenging reality for many people around the world. AUD is the most detrimental of these health conditions1. In this study, we examined how the central diagnostic systems' criteria (DSM) and guidelines (ICD) were related to two functional characteristics (FI and SD) as evidence of these systems' concurrent validity.

Our results must be regarded with some limitations. First, the small sample size makes it difficult to generalize these results to other populations. However, despite the small sample size, which can lead to confidence intervals close to 1 in regressions, the power for the correlations was above 0.80 in all cases, except for hazardous use, the number of events per variable required for logistic regressions was satisfactory21. Secondly, the data were collected almost exclusively from low-income patients, which introduces the possibility of other factors causing both FI and SD. In addition, this study was conducted in treatment-seeking patients, which limits the generalizability of the results to people with AUD who do not seek treatment. Finally, the mean age of the participants may have biased the results, as different age groups may have different patterns of alcohol use and experience diverse functional characteristics.

Despite these limitations, our results indicate that FI and SD grow as the number of DSM-5-endorsed criteria increases, meaning those with more severe AUD exhibit higher levels of FI and SD. However, we found that patients endorsing specific criteria were likelier to report SD than those who did not. Except for hazardous use, larger/longer, attempts to quit, activities reduction, and craving, we found every other criterion related to SD. The association between role impairment, interpersonal problems, physical or psychological problems, and SD could land on these three criteria’s potential to influence a person's everyday life. The relationship between the other three criteria (tolerance, withdrawal, and much time spent using) and SD can be explained by the fact that they may be more present among chronic patients with a long history of alcohol dependence.

On the other hand, a lot of time spent using is the only criterion associated with FI. This may be related to the measure we used to assess FI, the WHODAS 2.0. This instrument was developed by WHO11 to evaluate disability not only among people with AUD, but in a wide range of physical and mental conditions. As a result, the main domains it appraises may not entirely correspond to those affected among people with an AUD. In addition, endorsement of the much time spent criterion may imply less time available to perform correctly on several dimensions: self-care, participation in the community, relationships, and daily activities, suggesting this criterion might be an indicator of FI. Surprisingly, no other criterion was related to FI, perhaps indicating that patients could somewhat perform in different spheres of their lives despite their pathological consumption. Two non-exclusive rationales for this result may be the following: on the one hand, people with AUD may develop behavioral tolerance22, learning to perform despite being under the influence of alcohol or withdrawing from its effects; on the other hand, they might exhibit a certain degree of self-deception, which affects the assessment of their performance. Nonetheless, our finding of a moderate positive relationship between the number of criteria met and the level of FI suggests that those with increasingly severe levels of AUD report significant disability.

The differences we found in how individual criteria are related to FI and SD may be relevant for professionals addressing early detection of alcohol-related conditions and forward the understanding of the long delay in treatment-seeking observed among people with an AUD. Our findings also indicate that DSM-5 AUD's severity (by the number of endorsed criteria) will be more strongly related to the level of distress experienced by the person than to their performance on several life domains.

Noteworthy, we found none of the ICD-11 guidelines for Alcohol Dependence related to FI and only Impaired Control lightly related to SD. The lack of association between ICD-11 guidelines and FI is not unexpected because no criterion, except for much time spent using, was individually related to FI. On the other hand, in this classification system, the six criteria individually related to SD are mixed up with the ones that were not, which could account for the lack of association in our results.

In line with the findings from Mannes et al8, the presence of an AUD, according to DSM criteria, is associated with both SD and FI. However, no association was found between these two functional characteristics and any of the three ICD guidelines for Alcohol Dependence, except for the weak association reported between Impaired Control and SD. This finding is in line with the definition of AUD provided by DSM-5, in which impairment and distress are included as fundamental characteristics of this disorder5. Otherwise, ICD-11 does not emphasize the role of these characteristics in its Alcohol Dependence definition based on the internal drive to consume. Differences between both classification systems have already been explored5. Our results suggest that the DSM-5 AUD diagnosis performs better than the ICD-11 diagnosis in identifying those exhibiting higher levels of FI and SD.

Finally, we found a strong association between FI and SD. This association is stronger than the one found in a study performed with the general population13. This association may not be specifically related to alcohol consumption (since other factors, such as income level, may interfere). However, it provides relevant information regarding how treatment-seeking people with AUD perceive themselves in terms of how they perform in different life domains and how they feel. In this case, the detriment of significant life domains is accompanied by a subjective feeling of discomfort. This is in line with previous findings suggesting that individuals with a substance use disorder have a significantly diminished quality of life23.

In conclusion, this paper analyzed functional characteristics as evidence of concurrent validity for the DSM-5 and the ICD-11. We found that DSM-5 was more accurate in identifying those with higher levels of FI and SD in a clinical sample of Argentinean people with an AUD. This information can be of theoretical value for a better understanding of alcohol-related conditions and has practical implications for improving the quality of care, aiming to those with more FI and SD.