Introduction

The p-value is a topic of fundamental importance in epidemiology and research, despite its controversies and questioning1. Not only is it part of the statistical inference process based on hypothesis testing, at a critical level, p-value expresses the degree of comparability between the null hypothesis and the data, being specific the p-value is the probability associated with contrast statistics when the null hypothesis is true1,2. Moreover, it also allows a reflective process for decision-making in health and the critical analysis of scientific articles2.

However, studies in different parts of the world have found deficiencies in the knowledge of this. Horton et al.3,4 mention that health professionals have greater difficulties in understanding statistical methods, while Andreu et al.3) report that the prevalence, in Argentina, of low knowledge about p-values in doctors and therapists is 63%. Whilst in Peru, the Araoz-Melgarejo et al study shows that insight into statistical analyzes is low5.

Although most of the work is focused on knowing if the health professionals knew biostatistics6-10, it should be known how the understanding of the p-value, as a biostatistics’ tool, is independent, especially in undergraduate students. For this reason, the objective of this research is to determine the factors associated with knowledge about p-value in a sample of human medicine students.

Methods

Study design: Cross-sectional analytical study based on the analysis of a virtual questionnaire distributed from September 1, 2021, to October 1, 2021. Population, sample and eligibility criteria: The population was made up of 1192 medical students of both sexes, belonging to faculties of human medicine in Peru. Those who agreed to participate in the study and those who reported residing in the country were included. Those who were in the first, second and third cycle of the career (by standardization, due to the probability of not having taken the biostatistics course), those under 18 years of age, and those who did not adequately complete the questionnaire questions were excluded. Consecutive non-probabilistic sampling was carried out.

Variable definition: The questionnaire contained three groups of questions: The first part consisted of 8 sociodemographic questions that were age; sex; academy semester; external course in epidemiology, biostatistics or research; reading of scientific articles; type of university; if is the author of an article published this year and number of articles published. The second section consisted of 11 nominal questions (True/False/Don't know) about p-values. If the answer was correct, a point was awarded, while if it was incorrect, none was awarded. The result of this was categorized dichotomously, grouped into "sufficient knowledge" (≥ 6 points) vs "insufficient knowledge" (< 6 points).

Data collection and procedure: Given the national situation (COVID-19 pandemic), it was decided to collect the information virtually. The questionnaire was designed in Google Form. The test lasted about 10 minutes per person. This was distributed through the online survey on Facebook and Whatsapp, to contact university medical students.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analyzes were performed with STATA version 17.0 software. For the descriptive analysis, the qualitative variables were summarized in absolute and relative frequencies; while the quantitative variable was presented in the form of median and interquartile ranges, due to the non-normal distribution evaluated by histogram. In the bivariate analysis, the chi-square test was performed. Finally, a generalized linear model of the Poisson family with robust variance was performed to obtain the crude prevalence ratio (PRc) and adjusted (PRa) for the covariates mentioned above. It was considered statistically significant with the p-value <0.05 and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was presented.

Ethical aspects: Informed consent was given to all participants. The information obtained did not violate the privacy and integrity of the study participants, since they were filled out anonymously. The procedures complied with the ethical standards of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

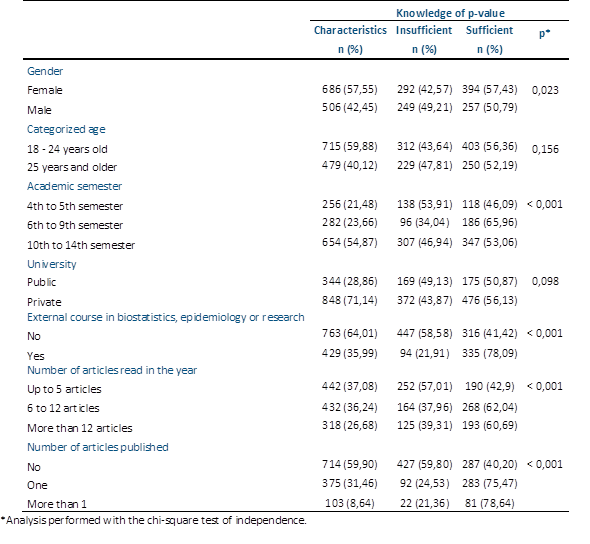

A total of 1192 students were surveyed. The 57.55% were female, while 54.87% were between the 10th and 14th cycle. Only 28.86% belonged to a public university. 35.99% took an external course in biostatistics, epidemiology or research and 54.69% presented sufficient knowledge about the p-value. Regarding the bivariate analysis, no statistically significant association was found with age (p=0.156) and university (p=0.098). The rest of the characteristics and analyzes can be seen in the first column of Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics and bivariate analysis of p-value knowledge in peruvian medical students (n=1192).

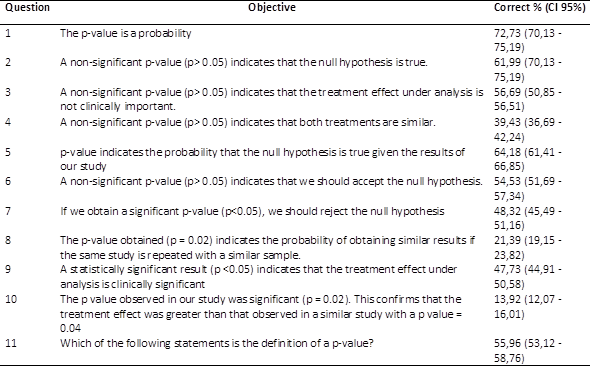

Overall, the question with the most correct answers was about the concept of p-value as probability (72.73%; 95% CI 70.13% - 75.19%), while the question with the least correct answers was about the interpretation of the p-value in a clinical analysis (13.92%; 95% CI 12.07% - 16.01%). The rest of the responses can be seen in Table 2.

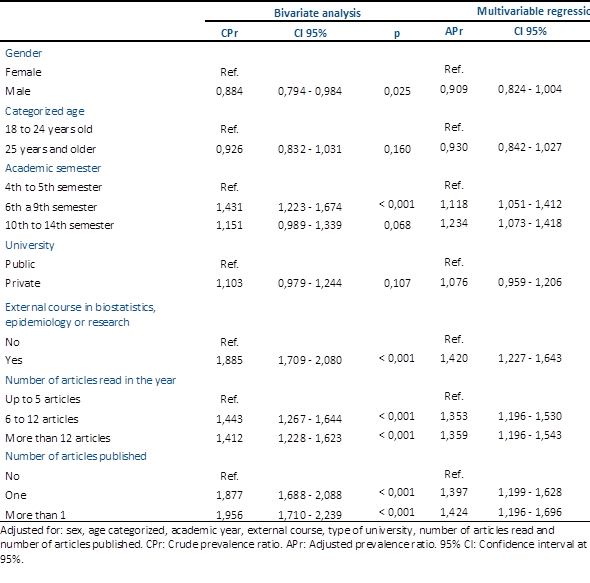

Table 3 shows the multivariate analysis of each factor associated with knowledge of biostatistics. The variables used for adjustment were gender, categorized age, academic cycle, external course, type of university, number of articles read, and number of articles published. A statistically significant association was found for those between the 6th and 9th cycle (APr: 1.118; 95% CI 1.051 - 1.412; p=0.009) and medical internship (APr: 1.234; 95% CI 1.073 - 1.418; p=0.003). Taking an external course in biostatistics, epidemiology or research (APr: 1420; 95% CI 1227 - 1643; p<0.001); having read 6 to 12 articles per year (APr: 1353; 95% CI 1196 - 1530; p < 0.001) and more than 12 articles per year (PRa: 1590; 95% CI 1313 - 1967; p < 0.001); and publish at least one scientific article (PRa: 1.397; 95% CI 1.199 - 1.628; p<0.001) or more than one (APr:1.424; 95% CI 1.196 - 1.696; p<0.001).

Discussion

It was evidenced that a little more than half understood the biostatistical results reported in the medical literature. This is the first study that reports the level of knowledge of the p-value for Peruvian medical students. Numerous investigations have studied statistical knowledge in human medicine students and medical residents11-13, but few have focused solely on the p-value, since in a circumscribed way, knowledge of this has been evaluated with only one or two questions, undervaluing or overvaluing this topic.

The percentage of students with sufficient knowledge was slightly higher than 50%. Although other studies have found that the values of ignorance of this topic revolve around 60%3,14,15, In general, the concepts of biostatistics in our environment are low5. Furthermore, the question that had the fewest correct answers was the one that requested an interpretation of the p-value, despite the fact that the majority knew the concept of the p-value as probability. Works such as Lecoutre et al.16 and Badenes-Ribera14) have found that there is a weakness in the interpretation of this. This also means that the lack of knowledge of the value p is more frequent to the interpretation than to the theoretical concept. This may be because when health professionals read scientific articles, they do not usually apply an interpretation beyond applying the p < alpha rule to know if there are statistically significant differences or not17.

Both age and gender were not associated with knowledge about p-value. The first should not, since the gender difference should not cause a greater or lesser knowledge of it, and it is consistent with what was found in other works3,6. In the case of the second, this may be due to the fact that it does not matter that they are older, if they have not studied the subject, they do not have to know this well3,16. No association was found between public and private universities, which also coincided with the work of Andreu et al.3.

With higher academic semesters, there have been several courses that request the need to understand the concepts of p-value, as in clinical courses, where published cases are discussed, so it allows you to learn more about the subject as you finish your degree. The Araoz-Melgarejo study had the same result when it evaluated biostatistical knowledge in medical students5.

Taking an external course in research allows the student to be instructed in the subject in a more focused way, first because it would not be a compulsory course, being voluntary on the part of the student, and, secondly, because these courses focus on deeper statistical topics18. The study by Andreu et al.3 found that the lack of training in scientific research methodology increased the probability of having less knowledge on this subject. Other investigations also found the same, although they were aimed at knowledge in biostatistics in a general way6,19,20. Furthermore, as more scientific articles are read and manuscripts are published, the understanding of the p-value is much greater. These results coincide with the works of Andreu et al.3, that reading less than 6 articles per year increased the probability of having less knowledge on this topic.

This study has limitations. First, the questionnaire was sent through internet media to obtain a good number of undergraduate students. Second, since a probabilistic sampling has not been carried out, it is likely that it will not be representative at the national level; however, given the characteristics that may be similar among students, some inference could finally be made. Thirdly, the cut-off was arbitrarily grouped to define with what score it can be said that you have sufficient knowledge and the opposite. However, the authors considered that the median plus one would be an adequate score, in addition to considering that a dichotomized value is of greater analytical understanding.